Gitmo Turned Its Inmates into Artists. Now, They Want to Send a Message.

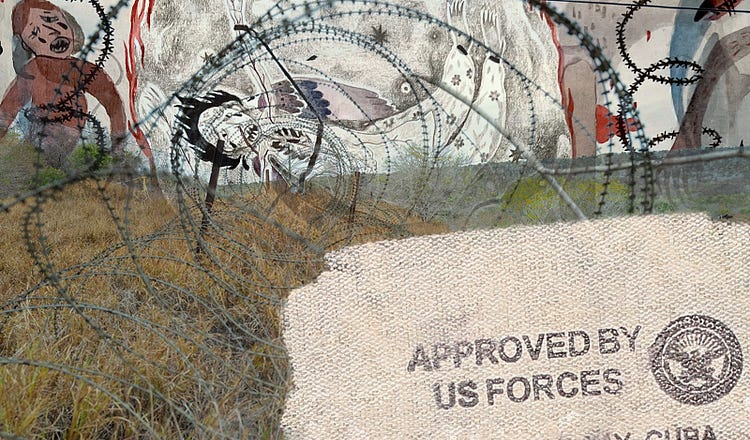

Photo illustration by The Free Press.

A story about the prison that will never close. The men who became artists inside it. And some uncomfortable truths about America.

470

GUANTANAMO BAY, CUBA — In September 2002, police in the well-to-do neighborhood of Gulshan-e-Iqbal, in the Pakistani city of Karachi, arrested a man named Ahmed Rabbani.

It had been a year since the September 11 attacks, and the Pakistanis, with the Americans, were rounding up people suspected of al-Qaeda ties.

Rabbani, then in his early thirties, appear…

Continue Reading The Free Press

To support our journalism, and unlock all of our investigative stories and provocative commentary about the world as it actually is, subscribe below.

$8.33/month

Billed as $100 yearly

$10/month

Billed as $10 monthly

Already have an account?

Sign In