What We Learned in 2022

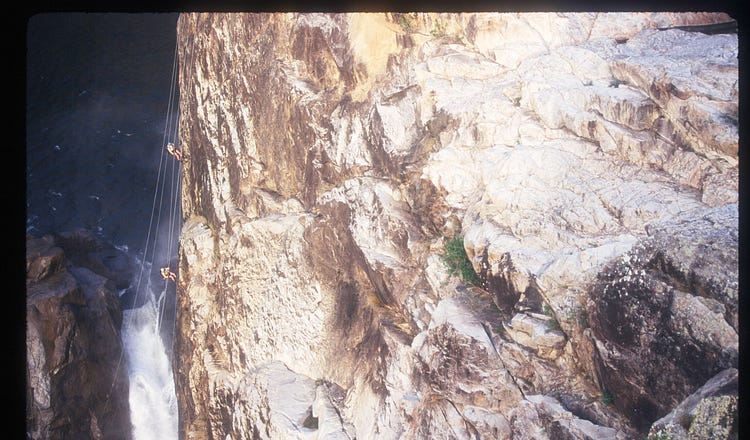

Two members of a team rappel down a cliff at Herbert Falls in Queensland, Australia. (Gilles Mingasson via Getty Images)

Sebastian Junger on underdogs. Thomas Chatterton Williams on self-restraint. Masih Alinejad on freedom. Jennifer Sey on marriage. And more.

450

As we prepare to bid farewell to 2022, the feeling that seems to course through our social media, our politics, and our culture these days is one of uncertainty, ambivalence and ambiguity. It feels like nothing is quite in focus. That a lot is up in the air.

With that in mind, The Free Press asked some of the most thoughtful writers we know: What did you…

Continue Reading The Free Press

To support our journalism, and unlock all of our investigative stories and provocative commentary about the world as it actually is, subscribe below.

$8.33/month

Billed as $100 yearly

$10/month

Billed as $10 monthly

Already have an account?

Sign In