The SAT Is Back. Or Is It?

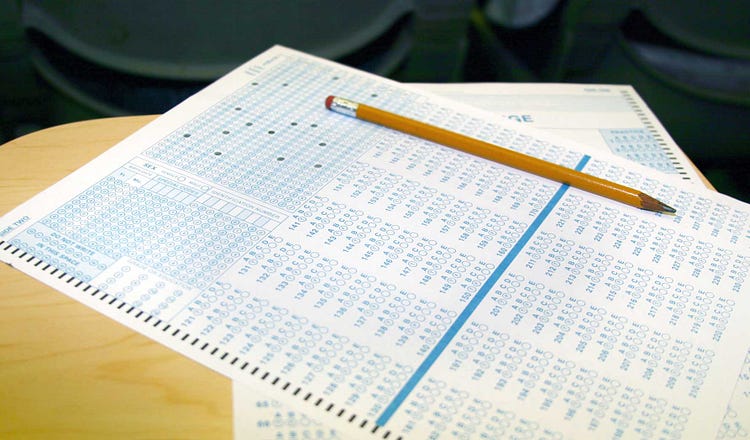

After nearly a century of pencil and paper, the SAT is going digital. (Getty Images)

Elite schools have reintroduced standardized testing—but does a new, all-digital exam mean standards will slip?

87

On a cold morning in December 2019, I woke up at 6 a.m., ate a light but energizing bowl of oatmeal and banana, and headed out to Brooklyn, my pump-up playlist blasting. I was about to take the SAT. Sitting in that classroom with my number two pencils lined up neatly, sharp as weapons, I had no idea that only six months later, Brown University, the scho…

Continue Reading The Free Press

To support our journalism, and unlock all of our investigative stories and provocative commentary about the world as it actually is, subscribe below.

$8.33/month

Billed as $100 yearly

$10/month

Billed as $10 monthly

Already have an account?

Sign In