Pride Month is almost over. Perhaps you didn’t notice it began, because corporate America has kept its mouth shut this year for fear of provoking right-wing boycotts or reprisals from the Trump administration. A vibe shift? Maybe for Target. But not for my fellow gays, as I learned at 10 a.m. last Saturday when they blocked off my street and started blasting Kylie Minogue directly underneath my apartment. This is what Pride actually is: an excuse for us to get publicly day drunk, ostensibly under the guise of commemorating the 1969 riots at the Stonewall Inn. This tradition has thankfully survived, and will continue to, regardless of whether or not Raytheon throws a rainbow filter over their Instagram logo.

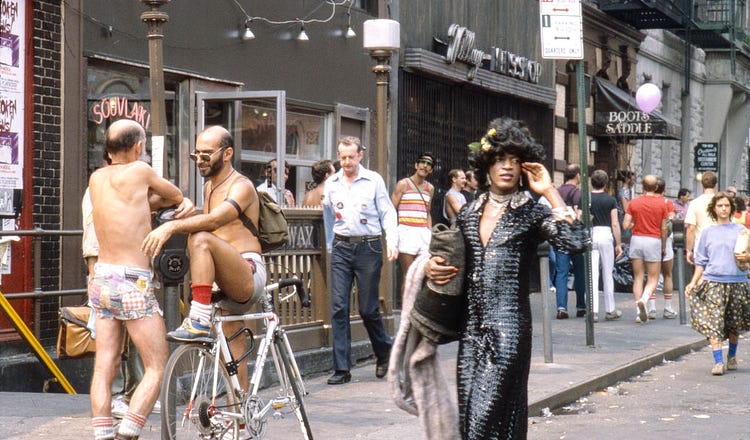

Less fortunately, another Pride tradition has also survived the right-wing moment: historical revisionism. Late last month, a transgender activist, author, and filmmaker called Tourmaline—f.k.a. Reina Gossett—released a best-selling book called Marsha: The Joy and Defiance of Marsha P. Johnson. The hagiography, which has received glowing reviews in publications like Allure, and ended up on The New York Times’ spring reading list, argues that the catalyst for the Stonewall riots—which essentially birthed the entirety of the gay-rights movement and paved the way for the last 70 years of gay culture—was actually a black trans woman called Marsha P. Johnson. In this narrative, average gay men and women are effectively sidelined in their own history.

Here’s Tourmaline: “No one knows exactly what happened on the nights of these raucous, wild clashes, but every historian of this period of LGBTQIA+ history agrees: Marsha P. Johnson was integral to the fiery resistance that took hold, and the movement wouldn’t have galvanized without her.”