To make proper sense of the bloody events of the past 12 months in the Middle East, I had to go to Vilnius.

That may strike you as bizarre, as Vilnius is the capital of Lithuania and roughly 1,600 miles from Tel Aviv. But Vilnius was once “the Jerusalem of the North”—that’s what Napoleon called it when he passed through in 1812.

It is a pretty city today, with all kinds of charming eighteenth- and nineteenth-century buildings, many of them creatively renovated since Lithuania regained its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. Yet Vilnius is a city of ghosts. That so much of its baroque architecture survived the brutalities of first Soviet, then Nazi, then Soviet occupation is remarkable. The Jewish inhabitants were not so fortunate.

To understand Israel today, you must first understand what befell the Jews of Europe. It is the story of what can happen to a people without a nation state. It is the story of a people without an army of their own. And it is a story of what could happen again if the enemies of the Jewish people are given a chance, once more, to fulfill their fantasies.

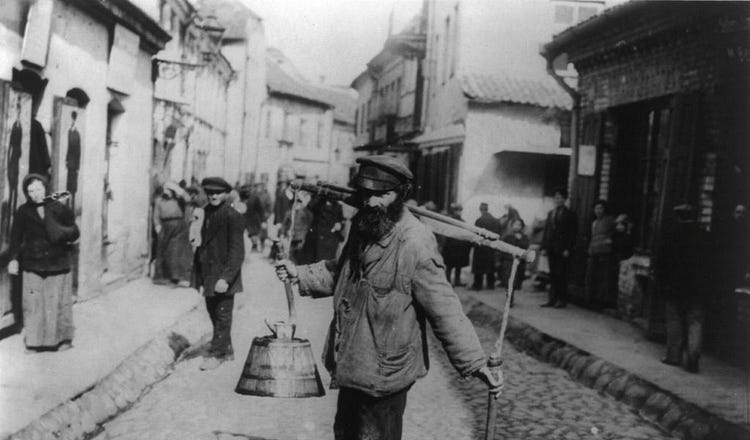

What today is Vilnius was once Vilna, a part of the Pale of Settlement in the Tsarist empire, and then, between 1918 and 1939, Wilno in the Republic of Poland. The condition of much of the Jewish population was impoverished and insecure. A British member of Parliament who toured the Pale of Settlement in 1903 was appalled by Vilna’s “pestilent” cellars.

Yet the city was also the most important Jewish cultural hub in Eastern Europe—a center of Jewish learning and culture from the 1560s until the 1930s. The greatest Talmudic scholar of the eighteenth century, Elijah ben Solomon Zalman, was known as the Vilna Gaon. The man who pioneered the revival of Hebrew as a spoken language, Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, studied in Vilna. That cultural vitality did not abate after the city’s incorporation into the Polish republic. YIVO, the center for Jewish studies that is now based in New York, was originally founded in Wilno in 1925.

In 1939, when Poland was partitioned between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, the city was handed over to Lithuania. This seemed providential. For Jews fleeing Nazi and Soviet rule, Vilnius looked like a sanctuary. Indeed, many of the city’s Jews celebrated the end of Polish rule.

But the celebration was premature. In June 1940, along with neighboring Latvia and Estonia, Lithuania was annexed by the Soviet Union. A year later, the regime changed once again—this time fatally.

With the German invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, the fate of the Jews of Vilnius was sealed. Between 190,000 and 196,000—more than 90 percent—of Lithuanian Jews were murdered: a higher share than in any other country the Nazis occupied. Their destruction was swift: Most Lithuanian Jews perished before the end of 1941.

Einsatzgruppe A was in charge of the “final solution” in Lithuania. But much of the killing in Lithuania was done by locals. The Jews of Vilnius were killed by their neighbors as much as by the invaders.

Nationalist underground posters proclaimed “the fateful and final hour. . . to settle our account with the Jews.” The most notorious Lithuanian perpetrators of the Holocaust were the Ypatingasis būrys (Special Squad), which was involved in slaughtering 72,000 Jews near the railway station at the Ponary forest (now Paneriai).

It was here that the Nazis first systematically murdered women and children as well as men. Most victims were marched from the city to Ponary and stripped before being shot. Gold teeth were yanked out. The killing squads piled the bodies into six large pits that had been excavated for oil storage tanks. It was such grisly work that the executioners had to be plied with alcohol by their officers. One German soldier who witnessed the slaughter could say only: “May God grant us victory because if they get their revenge, we’re in for a hard time.”

Almost no one escaped.

In his book Black Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning, the historian Timothy Snyder tells the story of Oswald Rufeisen, a German-speaking Zionist who had fled to Vilnius from Poland in September 1939 and survived only by concealing his identity and working for both the Nazi police force in Belarus and the Soviet interior ministry and secret police, the NKVD. Few other Jewish witnesses survived.

Rufeisen’s recollections depict courage, ingenuity, and sheer luck in the face of unspeakable horror. While working in Nazi-occupied Belarus, he gave the Jews in the Mir ghetto not only warnings of impending “actions” against them, but also weapons stolen from the German Security Police commander in Mir, Reinhold Hein.

“In Meister Hein’s room was a locked cupboard full of arms—rifles, pistols, and hand grenades,” Rufeisen recalled. “Each time I took one of them and placed it among the plants in the garden, and when evening fell I brought it to Yisrael Reznik at the ghetto gates. In this way I handed over 12 rifles.” A Jewish boy named Leibel Itzkowitz, who worked in the German stables, would come to see Rufeisen every day after work. He would leave with “a bag full of bullets covered with a small amount of food.”

But resistance to the Holocaust on this paltry scale was futile. When he heard from Hein that the “liquidation” of the Mir ghetto had been ordered, all Rufeisen could do was tip off its inhabitants to flee into the woods, and point the Germans in the opposite direction.

You will now see why, when I first saw the video footage of what Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad had done on October 7 last year, my first thought was of the Holocaust. I recognized immediately what the terrorists were doing. By murdering defenseless women and children, as well as men, they were enacting a trailer for a second Holocaust. The sexual violence that accompanied the massacre was also familiar. Rape—nearly always followed by murder—was a recurrent feature of the Holocaust, despite the strictures of Nazi legislation against “racial defilement.”