Dishonor Code: What Happens When Cheating Becomes the Norm?

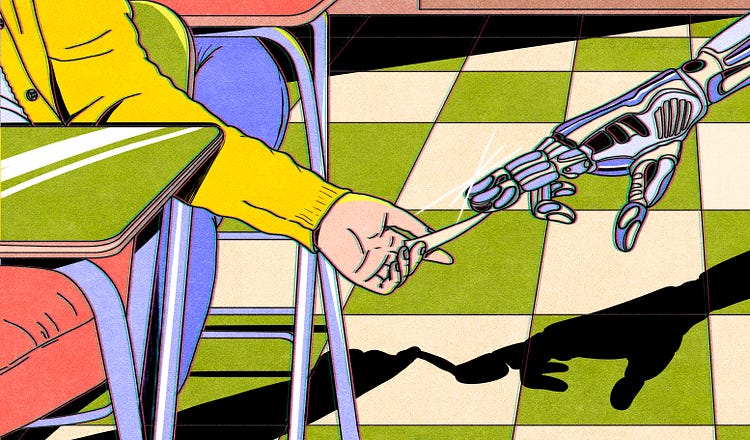

Illustrations by María Jesús Contreras for The Free Press

Students say they are getting ‘screwed over’ for sticking to the rules. Professors say students are acting like ‘tyrants.’ Then came ChatGPT . . .

681

When it was time for Sam Beyda, then a freshman at Columbia University, to take his Calculus I midterm, the professor told students they had 90 minutes.

But the exam would be administered online. And even though every student was expected to take it alone, in their dorms or apartments or at the library, it wouldn’t be proctored. And they had 24 hours to…

Continue Reading The Free Press

To support our journalism, and unlock all of our investigative stories and provocative commentary about the world as it actually is, subscribe below.

$8.33/month

Billed as $100 yearly

$10/month

Billed as $10 monthly

Already have an account?

Sign In