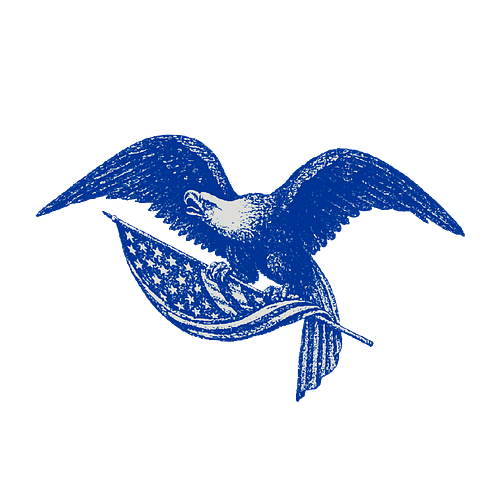

Elias Wachtel treks the Appalachian Trail, passing through the Great Smoky Mountains in Tennessee. (All photos courtesy of the author)

After graduating high school during Covid, it was hard to see a path. That’s when I decided to hike 2,193 miles.

340

When I was 18 years old, I decided to hike all 2,193 miles of the Appalachian Trail, from Georgia to Maine.

It was a strange year to come of age, 2020. Covid had canceled my high school graduation and delayed my freshman year of college; it was hard to see how to go out into the world and grow up. But from my bedroom in the suburbs of Chicago, there was…

Continue Reading The Free Press

To support our journalism, and unlock all of our investigative stories and provocative commentary about the world as it actually is, subscribe below.

$8.33/month

Billed as $100 yearly

$10/month

Billed as $10 monthly

Already have an account?

Sign In