For my whole career in finance, I have distrusted the obvious. And yet, for many years there was one number I assumed was an actuarial fact: the U.S. poverty line. Yes, I saw Americans feeling poorer every year, despite economic growth and low unemployment. But ultimately, I trusted the official statistics. Until I saw a simple statement buried in a research paper.

And I realized that number—created more than 60 years ago, with good intentions—was a lie.

The statement was this: “The U.S. poverty line is calculated as three times the cost of a minimum food diet in 1963, adjusted for inflation.” When I read it I felt sick. And when you understand that number, you will understand the rage of Americans who have been told that their lives have been getting better when they are barely able to stay afloat.

In 1963, Mollie Orshansky, an economist at the Social Security Administration, observed that families spent roughly one-third of their income on groceries. Since pricing data was hard to come by for many items (e.g., housing), if you could calculate a minimum adequate food budget at the grocery store, you could multiply by three and establish a poverty line. Orshansky presented her findings in 1965. She was drawing a floor, a line below which families were clearly in crisis.

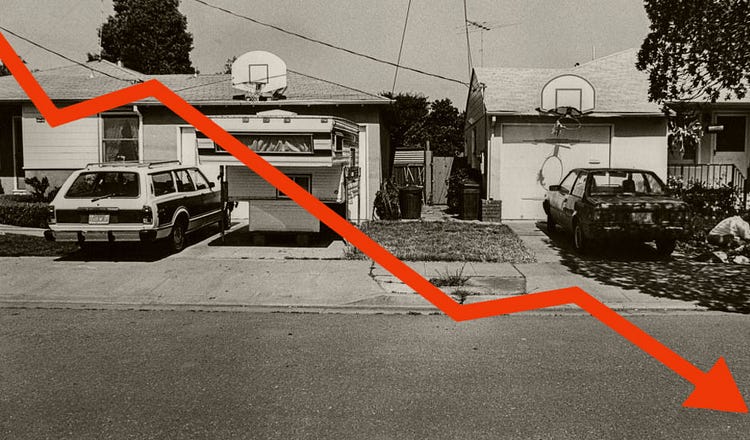

For that time, that floor made sense. Housing was relatively cheap. A family could rent a decent apartment or buy a home on a single income. Healthcare was provided by employers and cost relatively little (Blue Cross coverage cost in the range of $10 per month). Childcare didn’t really exist as a market—mothers stayed home, family helped, or neighbors (who likely had someone home) watched each others’ kids. Cars were affordable, if prone to breakdowns. College tuition could be covered with a summer job.