What Makes a War Just?

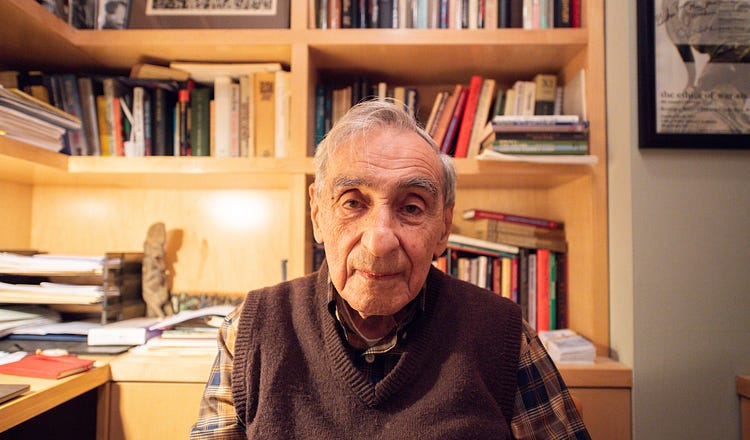

Michael Walzer at his home. (Jacob Kander for The Free Press)

‘It’s a situation where every decision is agonizing.’ A conversation with Michael Walzer, the author of ‘Just and Unjust Wars.’

125

Reports out of Gaza Tuesday that hundreds of Palestinians had been killed in a hospital blast—which now appear to be wildly inaccurate—underscored the debate coursing through the protests and proclamations surrounding Israel’s showdown with Hamas: Is this a just war?

And, assuming it is a just war, assuming Israel is right to strike back against Hamas, t…

Continue Reading The Free Press

To support our journalism, and unlock all of our investigative stories and provocative commentary about the world as it actually is, subscribe below.

$8.33/month

Billed as $100 yearly

$10/month

Billed as $10 monthly

Already have an account?

Sign In