The Free Press

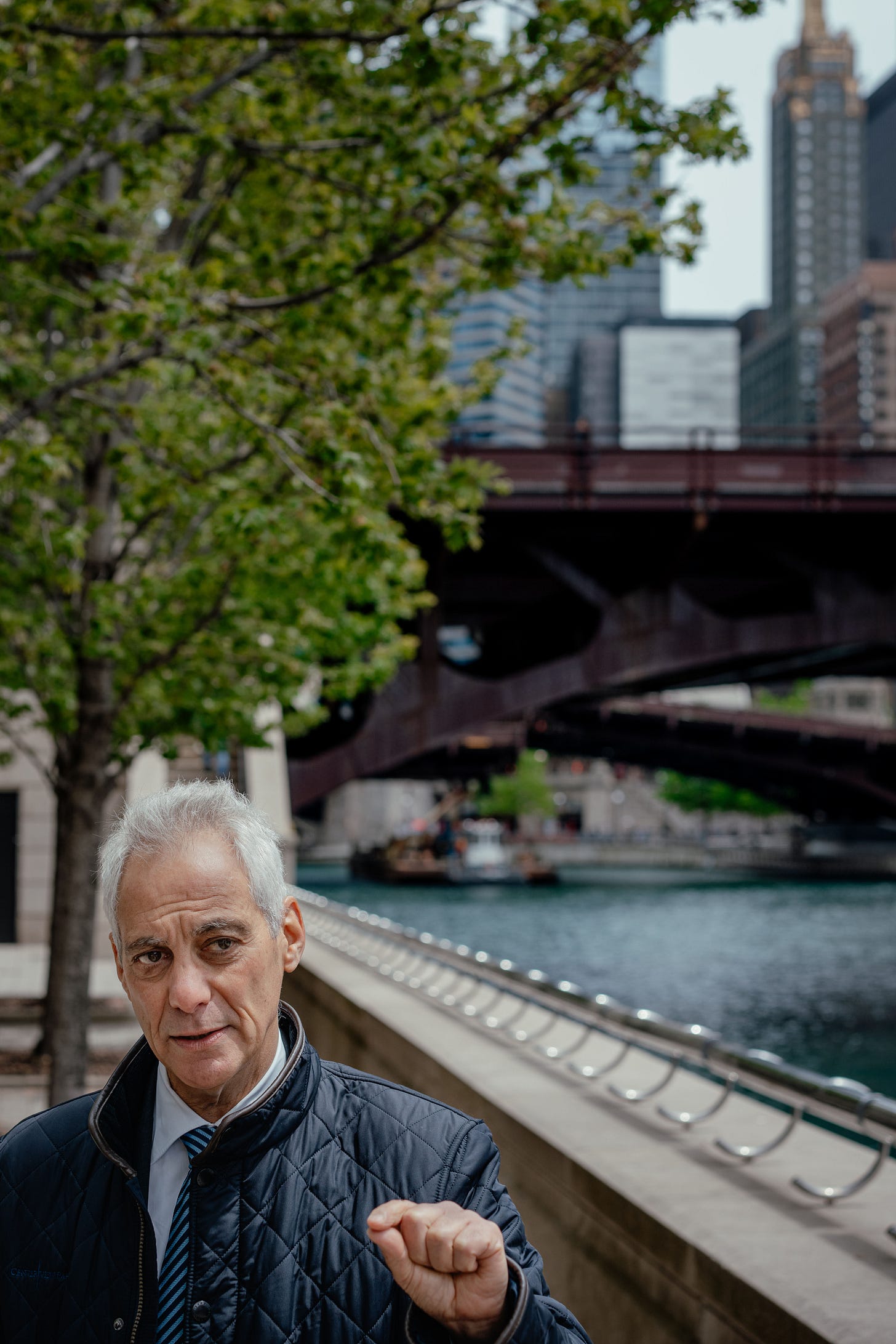

CHICAGO — We had just sat down in our booth at Pizzeria Portofino, an upscale restaurant on the riverfront he revitalized as mayor, when I asked Rahm Emanuel how he was doing.

“I don’t have prostate cancer,” he quipped.

There it was. Sharp, funny, a little nasty, a little glib—and aimed directly at the proverbial elephant in the room. Classic Rahm Emanuel.

I had come to Chicago because I wanted to know who was going to lead the Democratic Party out of its doldrums, and there were rumors—more than rumors—that Emanuel wanted to be that guy.

And he wasn’t exactly denying it.

It had been the most tumultuous weekend for Democrats since the discovery of the blue dress. Less than 24 hours before, former President Joe Biden had disclosed he had stage 4 prostate cancer that had metastasized to his bones. Two days before, an audio tape of Biden’s interview with former special counsel Robert Hur had been leaked to Axios; it made Hur’s conclusion that Biden was “a sympathetic, well-meaning, elderly man with a poor memory” seem generous. Meanwhile, Washington was still digesting the news, in a just-published book, that Biden’s closest aides—with a great deal of help from the White House press corps—had gone to great lengths to cover up the president’s mental decline.

The book fueled (not surprisingly) suspicion around the cancer announcement: How long had the president and his senior staff known he was ill? Had that, too, been hidden from public view?

That very morning, Emanuel’s older brother Zeke, the well-known oncologist who had once served as a medical adviser to Biden, had gone on Morning Joe to discuss the former president’s diagnosis. When Joe Scarborough asked him whether it was “likely” that Biden had cancer while he was president, he replied flatly, “Oh yeah. He did not develop [prostate cancer] in the last 100 days, 200 days. He had it while he was president. He probably had it at the start of his presidency in 2021. Yes, I don’t think there’s any disagreement about that.” In other words, Biden’s doctor was either woefully negligent, which seemed unlikely, or, that’s right, another cover-up.

Rahm Emanuel’s little prostate quip had—inadvertently—touched on his party’s No. 1 problem: Voters don’t trust Democrats. Even before the cancer announcement, Democrats were publicly wrestling with how to “regain trust with the American people.”

Emanuel, however, dismissed the question as almost beside the point. “We can’t get distracted by the cultural issues and lose sight of what Americans care about and what impacts them, which is a shot at the American dream,” he said. “We have to be able to stand up to the interest groups. We can’t look weak and woke”—he had recently started saying “weak and woke” a lot—“we need to be grounded and centered.”

When I asked Emanuel about a recent report that he was running for president, he told me that nothing—or, as he liked to say, “nuh-thing”—was etched in stone.

“Before I make a decision, I want to know that I have an answer to what I think ails our country, ails our politics, and ails the party—and they may all be the same answer,” he said.

But over the course of our nearly two-hour lunch, Emanuel sounded increasingly as if he had already decided. “I know what I want to do,” he said. “We’ve got to get ready to fight for America—and that’s what I’m going to do.”

When I asked former Democratic speaker Nancy Pelosi, who has known Emanuel since his days in the Clinton White House, whether he would run in 2028, she replied, “I think so.”

“I’m not done with public service,” Emanuel said. “I’m hoping it’s not done with me.”

He had been road-testing that line with other reporters and podcasters, working on the intonation, the pacing—like a comedian. Or a longtime pol mobilizing for the Big Show.

It was a tad confusing: On the one hand, the Democratic establishment had never come in for more deserved disdain and distrust. On the other hand, if there were ever a creature of the Democratic establishment, it was Rahm Emanuel.

Consider the résumé: senior campaign aide and then senior adviser to President Bill Clinton. Followed by a three-year investment-banking stint, during which time he raked in $16 million. Then three terms as a Democratic congressman representing the North Side of Chicago; Barack Obama’s chief of staff; mayor of Chicago; and, finally, ambassador to Japan under Biden. Josh Lyman, the deputy chief of staff on The West Wing, the most self-satisfied boomer television show in the history of network television, was said to be based on Emanuel. (His younger brother, the superagent Ari, was the basis for another television personality—Entourage’s Ari Gold.)

He had been in the White House when the North American Free Trade Agreement became law—and when, its critics insisted, the exodus of American jobs to Mexico commenced. He had been kind of, sort of, for the war in Iraq while on Capitol Hill. And he had been back in the White House, under Obama, in the aftermath of the financial crisis—when Obama refused to punish the bankers the way that Emanuel now says they should have been punished.

Now, he sounds like a populist. The friendly but brusque, cut-the-bullshit guy from the big city telling it like it is. Not so different from our current president.

“The system is fundamentally rigged and corrupt against the American people,” said this man who had benefited handsomely from that system. “It was true in 2016, true in 2020, true in 2024.”

Emanuel added: “There are things that are unique to 2016 but the undercurrent in ’08, ’12, ’16, ’20, ’24, the one constant, is the resentment against the establishment, because we have self-dealt us in, our kids in, and dealt everybody else out. And the system is broken and rigged.”

When I asked him what he meant by that, he said a lack of accountability at the very top, and then: “People keep getting the shaft and not a shot at the American dream.” Was he road-testing that line too?

“The party needs to say” that “you work for a living, you’re going to have a government that works for you. We’ve got to tell them we’re on their side.”

Emanuel said: “I’m a product of Bill Clinton.” Clinton, with Goldman Sachs’s Robert Rubin as his treasury secretary, was surely the most neoliberal president the country had ever had—meaning he embodied the emerging consensus around free trade and the deregulation of markets. Was it at all odd, I asked Emanuel, that here he was, Mr. Neoliberal Elite, now demonizing the elite? Wasn’t his career intimately intertwined with the rise of our Democratic-technocratic-Silicon Valley-Hollywood overlords?

“I don’t buy those labels,” he said, meaning “neoliberal.” “I think they’re cheap. I think they’re nonrepresentative.” In the course of his career, he told me, he had battled the NRA, Netanyahu, the big pharmaceutical companies, the Chicago “education establishment.” And Emanuel spearheaded free community college and free universal nursery school for 3- and 4-year-olds in Chicago. “If free universal pre-K, if that’s neoliberal, okay,” he said. “If that’s progressive, okay. I think it’s moving people forward.”

He added: “I don’t buy moderate versus left. I buy moving forward versus looking backward.”

It’s important not to forget: Donald Trump rose to power by convincing millions of Americans that they’d been screwed by the suits. It was a caricature of the past three decades, blaming all our many woes on free trade and China. But really, Trump was saying, it was the super-connected in D.C. and New York (and maybe Chicago) who had betrayed their fellow citizens on their way to the zenith of the great American power structure. People exactly like Rahm Emanuel.

There is a growing chorus of defenders of the neoliberal consensus who concede that while many Americans lost their jobs and the global forces unleashed by free trade have not been all constructive, it has done much more good than bad.

John Lettieri, the head of the bipartisan Economic Innovation Group, a Washington, D.C., think tank, made this point in a recent thread on X, in which he noted that NAFTA is “often blamed for destroying jobs, closing factories, and harming the working class,” but that, in fact, the free-trade agreement had ushered in “substantial wage gains” for those Americans.

All of which may be true, but Trump won not just because he could give a good stump speech, but because he spoke to a great deal of genuine loss and fear—the slipping away of an old America.

The dilemma that any would-be president must wrestle with today is whether to come down for or against the old assumptions. Maybe—instead of running away from Clinton and Obama to an angrier, Trumpier left-wing populism—Emanuel would be better served by defending them, I asked?

He seemed conflicted—or maybe he just wanted to have it both ways.

“At the end of Clinton’s term,” Emanuel said, “we had 300,000 more manufacturing jobs than when Clinton started, right?” (That figure is up for debate, but it is widely agreed that the economy expanded significantly under Clinton, with 18.6 million jobs created.)

But then, in a more subdued tone, he went on: “We took our eye off the ball—all of us took our eye off the ball. The risk and the opportunities of a globally competitive America were not equally shared.” Emanuel continued: “Peoria is not set up to compete against China by itself. La Crosse, Wisconsin, is not set up to compete against China by itself, right? Battle Creek, Michigan, is not set up to compete against China by itself. In the political system, both parties allowed that to happen.” He added: “Americans were left abandoned on the battlefield to fend for themselves.”

The result was that “the American dream is unaffordable. I think it is inaccessible. I think that has to be unacceptable to us.”

Emanuel added: “Peter and Rahm are going to do fine, and Peter and Rahm’s kids are gonna be fine. Not everybody’s kids are going to be fine, and we left them unprotected.” (He’d tried out a clunkier version of that on The View the week before.)

Actually, he had been defending the Democrats’ record—if only by way of omission.

The critical inflection points since the end of the Cold War, he believed, had not been NAFTA or China’s admission to the World Trade Organization—which Clinton had championed—but the Iraq War and the housing and financial crises of 2007 and 2008.

“You can’t understand America today without both the Iraq War and the financial meltdown,” Emanuel said. “In both cases, the people responsible were never held accountable.”

That was mostly George W. Bush’s fault, I said, but didn’t his old boss share some of the blame? After all, it was Obama’s Justice Department that chose not to prosecute any financial executives.

He agreed. “The system needed Old Testament justice.”

“Old Testament justice—,” I started to ask, but he cut me off.

“A banker should have been brought into the public square,” Emanuel said.

The big thing, the battle he lost, the battle that, to his mind, shifted the whole trajectory of the Obama administration, was the decision to prioritize healthcare—at the expense of financial reform.

There was a meeting in March 2009, he recalled. “I had to miss my son’s birthday,” Emanuel said. “I was supposed to go home, and I had to cancel.”

They were in the Roosevelt Room, in the West Wing. Obama, just two months into his presidency, was there and the question they were all debating was: What do we do next? Do we focus on healthcare or financial reform?

The domestic team wanted to get healthcare done stat. They knew it was going to be a monumental lift, and they thought they had a historic window. Now was the time to act.

Emanuel wanted to do financial reform first. The economic team—starting with Timothy Geithner and Larry Summers—wanted to get a bill wrapped up ASAP, because, they said, “The industry won’t lend until they know the rules.” The economy was only just starting to crawl its way out of the dark. Without this help—now—“it would make a bad problem worse.”

But Emanuel’s reasoning was different. He was thinking about the politics.

“My point was: After passing the TARP”—the Troubled Asset Relief Program, which doled out some $475 billion to bail out the banks—“which was passed under Bush, but we’re implementing it, the country needed some sense that those who made a mess were going to be held accountable. If you did financial reform, the bankers would be fighting you, and that’s a good thing. The country would see you fighting for them, and holding accountable the people responsible for you losing your home and putting the economy upside down.”

If the administration did healthcare first, Emanuel said, “You were going to drown your political account down to zero. But fighting the bankers you were going to be putting capital back in your political account.”

Ultimately, of course, Obama came down on the side of healthcare.

“Healthcare took all the oxygen,” he said. “It was front and center for 16 months.” The following year, the Democrats pushed through the Dodd-Frank Act, which did establish a series of important financial reforms. But Emanuel thought the moment had been lost.

“Did you get the political punch out of it?” he said. “No—you missed it.”

When I asked Emanuel whether Obama had ever privately voiced regret to him, given Trump’s 2016 win, he sidestepped the question: “At the end of the day, you have Obamacare, and that’s a big deal.”

He is 65, which was a little hard to believe. To anyone old enough to remember the 1992 presidential election, Emanuel would always be the young Turk, the hyper-partisan, hyper-competitive brawler who, in the celebratory days following the election, famously yelled “Dead!” while stabbing a steak knife into a table and rattling off a list of former Friends of Bill—pols, donors, journalists—who had apparently wronged the campaign.

He had mellowed a bit since then (although he still swore like George Carlin). The last time I interviewed him he was running the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee—that year, 2006, he helped his party retake the House for the first time in 12 years.

He had also expanded his view of things. Temperamentally, he still seemed like a big city mayor, but he had just come back from Japan, where he had served for three years as ambassador during the Biden administration. He was more attuned to the world, East Asia, Xi Jinping, economic espionage, the Chinese crackdown on the private sector. He could see how Americans’ misunderstanding of China—including its 2001 WTO admission—had exacerbated our own problems.

“America was late to that awareness,” he said.

Now, he was home in Chicago. “I always come back home,” he said. His son and two daughters were in their twenties, and he and his wife, Amy Rule, were in their old house north of here, in Ravenswood.

His mother was about 25 minutes away. His father, Dr. Benjamin Emanuel, who had been born in Jerusalem, died in 2019 at the age of 92.

I asked him whether someone with his biography could win the Democratic nomination. It wasn’t just that he was part of the Democratic establishment. It was that he was a Jew with the middle name “Israel,” and he was unequivocally supportive of the Jewish state’s right to exist. According to a recent Gallup poll, Democrats support the Palestinian cause three-to-one over Israel. Among Americans ages 18 to 29, 33 percent sympathize with the Palestinians versus just 14 percent who support Israel, a Pew survey showed. Had he not seen the anti-Israel protests that had engulfed so many college campuses? Had he missed the blurring of anti-Zionist and antisemitic sentiment among the young? Had he not seen Democratic pollster David Shor’s finding that Jewish college students, irrespective of political bent, worried more about left-wing than right-wing antisemitism?

“When I ran for Congress in the Fifth District,” he said, “here were my predecessors to that district: Dan Rostenkowski, Rod Blagojevich, Flanagan”—he meant Michael Flanagan. “The current congressman is Mike Quigley. So who doesn’t fit in that lineage? Rahm Israel Emanuel.” He laughed. “I was running against a Polish woman, so, you could argue, it was stacked against me. And then I won, and I improved my margins every year.”

“Right—,” I started to say (but was cut off), but that was a story we had heard many times before, about candidates transcending their minority status and appealing to a shared Americanness, and it reflected the decency and strength of the republic (and the power of partisan politics).

“I do believe the country and the Democratic Party can and will—could nominate, rather—a Jewish candidate,” Emanuel said.

He didn’t think having a father who had served in the Zionist pre-independence paramilitary, known as the Irgun, would be problematic on the trail.

In fact, he said, “I happen to be the only person in the field who Bibi Netanyahu, in 2009, called a self-hating Jew, publicly.” He added: “I didn’t need a war to know this guy was the wrong guy.”

On Thursday morning he tweeted a brief, two-part statement in response to the shooting, the night before, in Washington—which left two Israeli Embassy staffers, both Jewish, dead.

“Amy and I want to share our deep condolences to the parents, the families, and the friends of Sarah Lynn Milgrim and Yaron Lischinsky, who lost their lives in the nation’s capital last evening,” he said.

This was followed by: “To be frank, it’s getting very old, trite, & far too frequent to say there’s no space for violence after every violent political act.” And then, somewhat enigmatically: “If we want to be honest with ourselves, we need to have a hard conversation with some difficult questions about why, why now, & why these people.” Emanuel did not mention that the suspect, Elias Rodriguez, had been spotted protesting in front of Emanuel’s house in Chicago in 2017 when Emanuel was mayor. (The protesters opposed the opening of a major Amazon facility in the city.)

He did not think of himself as enigmatic. “I’ve shown I’ve got the strength to say my views, and one of the key things about being a president is you got cojones, and you got strength,” he told me.

He added: “I’m not naive to antisemitism. I’m not naive to certain elements within the left.” His point—about winning his House seat and being elected mayor—was that the people, the voters, mattered the most, and he believed that, in the end, they would be on his side. “There’s going to be people who try to bring up stereotypes or other types of things, and I’ve never hid my Judaism—not gonna—but I have confidence in the public.”

Emanuel recalled: “When I was in Japan—we have a family cottage in Michigan—and somebody had spray-painted Nazi, antisemitic stuff on our fence, and a neighbor, unbeknownst to me, cleaned it up the next day.” He paused. “Never came forward—still hasn’t come forward. I’d like to know who did it.”

For more on Democratic party politics, read Rep. Dean Phillips on the Biden cover-up: