Welcome back to Douglas Murray’s Sunday column, Things Worth Remembering, where he presents passages from great poets he has committed to memory—and explains why you should, too. To listen to Douglas read this week’s work, from Lord Byron’s “Don Juan,” click below.

If Stephen Spender, my subject from May 7, had any group of poets in mind when he wrote about the truly great, then it was most likely the poets we now refer to as the Romantics.

How do we know that Spender had poets like Keats, Shelley, and Byron in his mind? Most of all because of those final lines that summon the image of Icarus. Those who travel toward the sun, burn up, yet leave the air “signed with their honor.”

Such was not the habit of all poets throughout history. It wasn’t even the case with all the Romantics (certainly not if you include Wordsworth), but it was with most of them. If anyone burned bright, aimed high, and burned up, then it was the great English poets of the early nineteenth century.

Among them was perhaps the only poet who could equal the Earl of Rochester in terms of reputation.

George Gordon, Lord Byron, was an infinitely greater poet—indeed one of the greatest pyrotechnicians in the history of poetry. Still, every bad reputation that a poet can acquire he acquired in remarkably short order. After a pretty dissolute childhood, he grew into an even more dissolute man, becoming famous overnight with the appearance, in 1812, of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage.

After that, he set about developing his celebrity in a way that now seems rather modern, though it would scandalize our current era perhaps even more than it did his own. I once lived at the same address as Byron in London, and can’t deny that I enjoyed the loucheness that came even from such posthumous proximity.

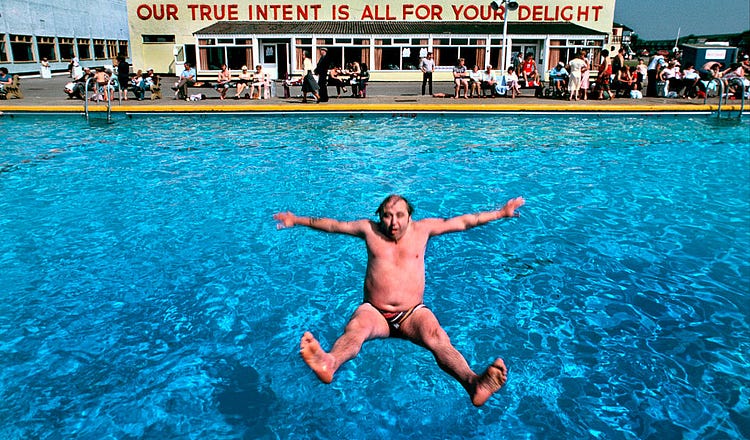

For Byron had that desire—described in the film Dead Poets Society—to suck out all the marrow of life. He did everything: he pursued sex, whored, fought, gambled, swam, sought to break every barrier and capture life in full, and then scorch it onto the page.