The Free Press

Long after it was promised, this week Harvard released its antisemitism report under pressure from the Trump administration. It is 311 pages. Harvard needed more than 300 pages to detail the Jew-hatred festering on its campus.

This was not, in other words, a sudden outbreak of antisemitism.

Let’s skip over the history—the quotas; the Soviet-sponsored “Zionism is racism” canard that exploded on campus in the 1990s; the guest speakers, like Leonard Jeffries, who had many theories about Jews’ world domination. Because the history is long. As far back as 1922, the governing board of Harvard unanimously voted that there was a “Jewish problem.”

Let’s start the clock with what I saw in the year I was at Harvard as a visiting scholar.

I attended my first Jewish event at the Divinity School on the holiday of Sukkot in the fall of 2023. The ceremony began with a speaker reassuring us, “This is a safe space for anti-Zionists, non-Zionists and those struggling with their Zionism.” In other words: not for me.

That happened one week before the attacks of October 7, 2023.

Hamas leaders have reportedly bragged that they have allies on campus. Who knows if they mean that literally or seriously? What I know, because I saw it myself, was that the Hamas massacre intensified hatred against Jews on an already hostile campus.

In posts on Sidechat, a campus social network, student comments ranged from “She looks as dumb as her nose is crooked” and “We got too many damn Jews in state supporting our economy” to far more sinister comments: “Decolonization is not a metaphor” (with Jewish blood dripping from the text). There were endless references to “Judeo-Nazis,” including by tutors in a student house, and swastikas made frequent appearances.

Students were insulted, shunned, harassed, and hounded in a hundred ways. An Israeli student was mobbed and assaulted at a “die-in” protest days after October 7. “Privilege trainings” for Jewish students were run by the university. Another student, a former soldier in the Israel Defense Forces, told me she was afraid to walk alone to her dorm room. Students were ghosted by longtime friends for expressing sympathy with Israel; one was told by friends it would hurt their careers to “associate with a Zionist.” Professors, in courses on Israel, removed all Israeli sources from the syllabus. Required reading in a Public Health course titled Settler Colonial Determinants on Health teaches that “Zionism manipulated Judaism as a religion to reinterpret history and redefine Jewishness in terms of ethnic belonging.”

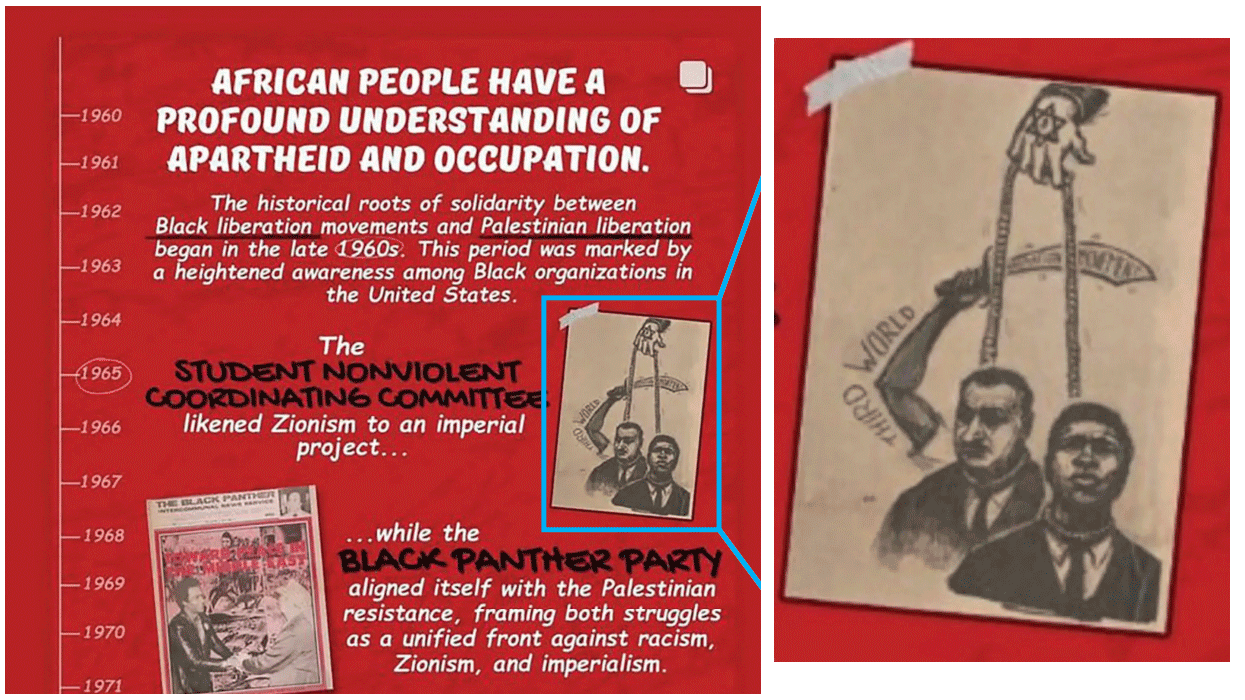

So as anxious students flocked to my office, I was shocked but not surprised to see the hostility continue unabated. There was memorably a cartoon posted by a Harvard faculty group on Instagram showing a Jewish hand hanging an Egyptian and a black man—a retread of a cartoon from the 1960s that was condemned at the time by black leaders as antisemitic. This cartoon was, to quote the report, “circulated by groups of pro-Palestinian Harvard students, staff, and faculty on social media.” Faculty! That is Harvard in 2024.

It is to the great credit of the report that it does not minimize or elide the ugly face of Jew-hatred that I saw repeatedly in my year at Harvard.

Critically, the report also explains the ideological roots of the abuse. It explains that anti-colonialism has become the ideological battering ram to mobilize a diverse cult of anti-Western sentiments. The challenge to Zionism becomes a first step in turning disillusion with the West into a wholesale indictment of it. The old antisemitism of the Soviet Union had this double purpose as well—destroy the Jews, and you’ve destroyed the root of Western civilization. Harvard is not just a host for this worldview. It is the dominant view on campus.

But what no report can capture is the feeling that Jewishness was something to hide, and the stigma of being a Jew-hater was fading. One student in my class, after having walked through Harvard Yard and being screamed at by some of the protesters, said to me: “They don’t just hate what I believe. They hate me.”

I taught as a visiting scholar in Harvard Divinity School—which is singled out, as it should be—for special censure. The Religion and Public Life program became “a focal point for concerns about one-sidedness and the promotion of a specific political ideology under the guise of academic inquiry.” Religion and Public Life commenced a six-year program inquiring into Israel-Palestine (since that is the only issue) with no real instruction in Judaism, a Zionist perspective, or Palestinian terror. The only people invited to speak were either explicitly anti-Israel or Jewish professors on the very far left of the Israel debate.

I was, you could say, a diversity hire: I was there explicitly to provide an alternative perspective. It says everything about the state of Harvard that the view shared by the vast majority of 16 million Jews is considered fringe.

Save a discussion before October 7, 2023, on Zoom with a pastor about forgiveness in our traditions, not once did the Divinity School ask me to present anything. Not once. Meantime, the Religion and Public Life program, an integral part of the Divinity School, was a nonstop parade of anti-Israel speakers without rebuttal.

My class (“Sources of Jewish Spirituality”) had both Jewish and non-Jewish students, but with the exception of one or two, none would speak up publicly about anything on campus. As one student in another class explained to me: “I don’t want to put a target on my back.” There are untold numbers of stories like this. (Indeed, in 2022, 83 percent of Jewish students said they experienced anti-Zionism on campus and 69 percent said that their Judaism or Zionism made them self-censor. That was before October 7.)

You might imagine that the 2023–2024 school year was rock bottom, but things continue to unravel. What the report does not note is the September 2024 introductory address of the new dean of the Divinity School, Marla Frederick. This is after all the so-called reckoning—after the congressional hearings, after Claudine Gay resigned as Harvard’s president in January 2024.

Here is a paragraph from Frederick’s address:

“These are just a few, brief, incomplete examples of monumental historical events that have shaped the lives of so many. The Maafa, the Trail of Tears, the Holocaust, the Nakba. It is impossible to compare the real human toll of devastation. And my point is not to engage in endless comparisons,” said Frederick.

But, of course, she already had. The disclaimer is drowned out by the vile juxtaposition of the Holocaust and the Nakba. “Endless comparisons” indeed. The disclaimer drowns beneath the odious juxtaposition. Those two unspeakable tragedies: Auschwitz and the founding of Israel. Not that I’m comparing, of course.

This false moral equivalency is everywhere at Harvard and places like it. And it was present this past week, too. The antisemitism report was published concurrently with a report on Islamophobia. (It is worth noting that according to the FBI’s 2023 Hate Crime Statistics, 68 percent of all religion-based hate crimes were committed against Jews, and 8.7 percent against Muslims.)

Any American of any religious stripe or political denomination should condemn any bigotry toward another group. Full stop. And I don’t doubt that Muslim students felt uneasy or even rhetorically attacked. But the idea that the venom directed against the two groups was in any way equal, or equally motivated, is absurd.

For example, the Muslim students in the Presidential Task Force on Combating Anti-Muslim, Anti-Arab, and Anti-Palestinian Bias report complained of the perils of wearing a keffiyeh. (“I was harassed when I wore a keffiyeh at my . . . work-study job”). I do not doubt that this occurred—and perhaps on many occasions. In my observation however, the keffiyeh was the fashion accessory of the season, whether you hailed from Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, or Greenwich, Connecticut. You could not walk across campus without seeing scores of students and some faculty in a keffiyeh, among the far, far fewer kippot and Jewish stars. At one point, the statue of John Harvard was draped in a keffiyeh; I never saw him wrapped in tefillin.

There was also a striking asymmetry of action: Zionist students did not camp out in Harvard Yard; they did not break into classrooms; they did not come with bullhorns (as I myself witnessed) into local restaurants and chant in Arabic, “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be Arab.” Their teaching assistants did not offer passes on exams to attend rallies, or attend rallies with them. They did not insist on wearing masks outdoors, so they could yell slogans with impunity. They did not continually yell slogans in the yard after they were understood to be eliminationist.

The Jews did, however, gather to light a Hannukkiah in public.

The public doxxing of Muslim students in mid-October 2023 by a truck (which came from outside Harvard) was egregious and should not have happened. Yet even in objecting to slights and slurs, the Islamophobia report itself somehow includes toward the end a deliberation about adopting Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) policies, as if anti-Zionist activism was an expression of Muslim safety. Welcome to the fun house mirror of what a past president of Harvard told me was the “world’s most important NGO.”

These two reports should not have been issued in tandem; it is an example of “bothsidesism” on steroids.

The antisemitism report has some important recommendations on admission, encouraging a more ideologically pluralistic and tolerant student body, creating rules for protest, and offering ideas for building a genuinely diverse community.

But what the report offers no solution for is that there is a deep ideological commitment among much of the faculty—particularly in the humanities and social sciences—that is anti-Western, anti-Israel, and often antisemitic. The Islamophobia report mentions “donors” (read: Jewish donors) who influence policy, but the antisemitism report does not focus on millions flowing from places like Qatar. The confluence of Islamism, old-line Christian antisemitism, and hard progressive antagonism to the Western and Israel project produced a perfect storm in places like Harvard Divinity School. Without a vast unlearning—among the faculty, not just the students—all the reports in the world will not change the atmosphere on campus. We will only be spraying perfume on a sewer.

I spent a year on a campus where, despite wars across the globe and hundreds of millions of literal slaves in the world from North Korea to Mauritania to Eritrea, America’s racial divisions, gender questions, and the plight of the Palestinians were the only issues that gripped the conscience of students and faculty. Remember the days when people cared about Tibet? It seems a relic from another moral century.

In our new and inverted one, the principal speaker at the 2024 commencement exercises was Maria Ressa, a Filipino American journalist and recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize in 2021. During her address, she deviated from her prepared remarks to say: “Because I accepted your invitation to be here today, I was attacked online and called antisemitic by power and money, because they want power and money.”

Two days before, on May 21, Sunn m’Cheaux, a Gullah teaching fellow in Harvard’s African Language Program, delivered the faculty keynote at the Affinity Celebration Honoring Black Graduates. In his address he said, “Zionist overlords starve Falastini infants to death?” Moments later, Dean Frederick of the Divinity School accepted an award on behalf of Claudine Gay, making no reference to the remarks that preceded her.

Sometimes the most chilling sound in the room isn’t the speech. It is the silence that follows it.

For more coverage on Harvard’s Antisemitism report, read here:

Harvard University released its long-overdue report on campus antisemitism exactly 10 days after Trump officials demanded to see it. The findings are disturbing.