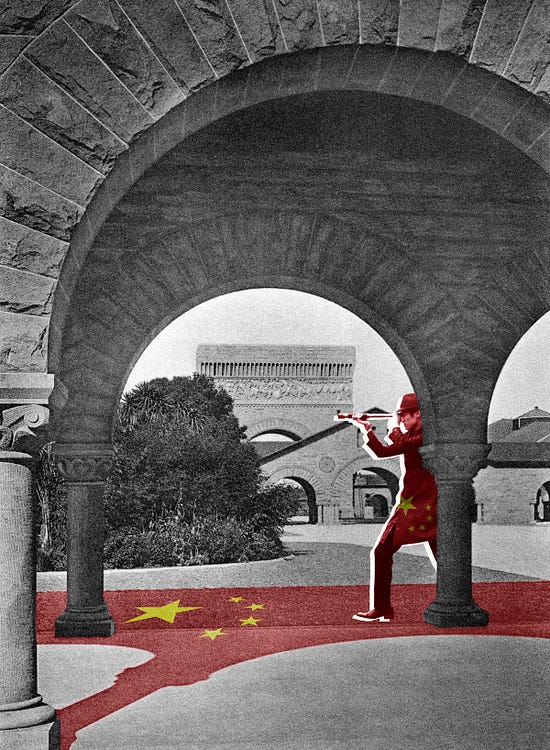

There have been hundreds of stories in recent years about China’s efforts to use its vast intelligence-gathering apparatus to steal America’s military and technological secrets. But there has been much less written about how that apparatus operates on elite college campuses. It was precisely that void that prompted two Stanford sophomores, Garret Molloy and Elsa Johnson, to try to document China’s intelligence-gathering at the university. Their story in The Stanford Review, which we are reprinting, offers a rare glimpse into how China spies, with chilling implications for U.S. national security.

Last summer, a man calling himself Charles Chen approached several Stanford University students, unsolicited, using social media. They were almost all women, and they were invariably researching China-related topics. One of them was Anna, a Stanford undergraduate student working on sensitive subjects linked to Chinese economic and military developments. At first, Chen’s outreach seemed benign; he asked about networking opportunities. But soon, his messages took a strange turn.

Chen inquired whether Anna, who requested anonymity fearing repercussions, spoke Mandarin. He sent videos of Americans who had gained fame in China. He encouraged Anna to visit Beijing, and even offered to cover her travel expenses. He sent screenshots of a bank account balance to prove he could buy the plane tickets. He also advised her to enter China for only 24 to 144 hours—short enough, he said, to avoid visa scrutiny by the government.

As Chen’s DMs grew increasingly persistent, he urged her to communicate exclusively via Weixin, the Chinese version of WeChat, a platform heavily monitored by the Chinese Communist Party. He mentioned things he knew about her that she had never told him. And he asked her to delete screenshots after commenting on one of her social media posts. By then, Anna knew that the situation she had found herself in was serious.