The Black Activist Trying to Save Oakland from ‘Phony’ Woke Progressives

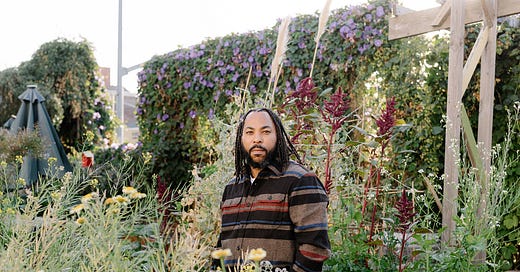

Seneca Scott at the Bottoms Up Community Garden in Oakland, which he runs. (Photos by Jason Henry for The Free Press)

Seneca Scott says his city and its leadership are broken. He has a plan to fix both.

237

Cardboard boxes of fresh yellow squash sit on a table outside the Bottoms Up Community Garden in Oakland, California.

Seneca Scott said “meet me at my office,” and this lush spot at the corner of 8th Street and Peralta—home to songbirds and clucking chickens—is it.

A few minutes later, Scott, 44, drives up in his Jeep and hops out wearing pajamas, a down …

Enjoying the story?

Enter your email to read this article and receive our daily newsletter.

Already have an account?

Sign In