In Monday’s column I wrote about the very public schism in the Beckham family, between the parents (David and Victoria) and their son Brooklyn, who announced on social media last week that he was no longer speaking to them. I explained that this situation is surprisingly common—that 11 percent of moms over 65 are not speaking to at least one of their kids, as well as 26 percent of dads. Yet, like a death, estrangement feels uniquely sad to everyone experiencing it. The column got a lot of reaction for this very reason—and many of you shared your own family estrangement stories in the comments.

I don’t know the inside details of the Beckham case, of course, but it sounds a lot like the kind of intergenerational conflict I hear about all the time, from both aging parents and adult children. And the cause is very clear: The parents and their kids never developed a fully adult relationship.

When kids are little, they are helpless and totally dependent. That creates an asymmetrical relationship with their parents, which is as it should be. But some families never progress beyond this relationship, even after their kids are grown. You probably know parents who treat their kids as incompetent even in young adulthood, second-guessing all of their decisions and condemning their life choices—all while, all too often, funding their lifestyles, at least in part. This foments dependence: Kids see their folks as walking ATM machines long after they could already be completely independent. If mom and dad are paying the family phone plan, why rock the boat?

This leads to coldness and mutual resentment, if not outright schism. That shouldn’t surprise us: Kids deserve to be treated like no-kidding real adults, and their parents deserve to be treated like actual loved ones, not parent-shaped Pez dispensers.

So what’s the solution? The advice I give people my age is to adopt a nonjudgmental interest in their adult kids’ lives without intervening—unless invited. This can be incredibly hard, especially when it involves a breach of values. A common example is an adult child not practicing the family’s religion. (In that case, here’s my advice: Bug God about them; don’t bug them about God.) Or, they might hold radically different political views. (Take a sincere interest in their views, especially if they are strange to you.)

As for young adults, the advice I give is to become truly independent. Like, get your own Netflix account (gasp!). When this happens, love actually feels more like a free act and less like an obligation in exchange for filthy lucre. It might even motivate you to take an actual adult interest in those weirdos you call your parents.

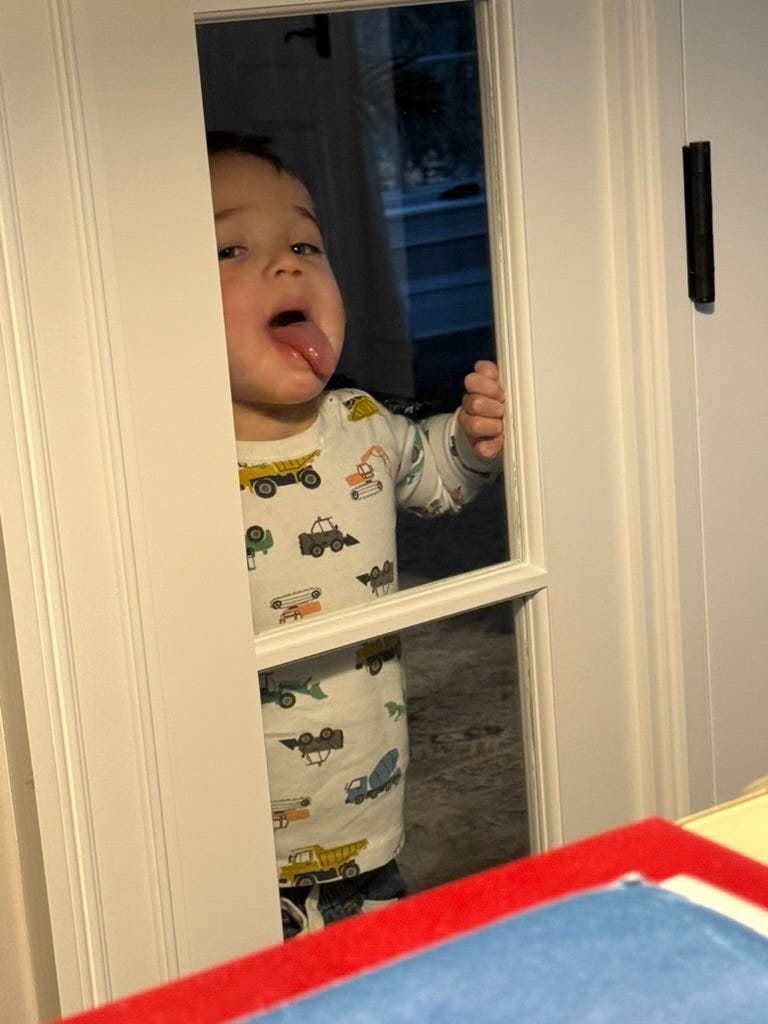

If you are wondering how we try to practice what I preach in my own family, I’ll tell you in a few weeks in a column I am writing about deciding to live in an intergenerational household. Speaking of, here is my roommate-grandson licking my home office window as he impatiently waits for me to wrap up this newsletter so we can wrestle. The boy knows his rights.

Off to wrestle. See you next week,

Arthur

PS: Be sure to check out the latest episode of my show Office Hours. This week I am joined by Dave Ramsey, one of the most influential voices in personal finance, whose work has helped millions of people change their relationship with money. Most people assume that having more money will make them happier. The research suggests something more subtle: What matters is not how much money you have, but how you use it.

While I am all for creating independence, there is no such thing as "one size fits all" advice. JMO.

Friendly feedback: ‘ATM Machine’ is redundant.