When the news came this week that Teen Vogue would be shutting down, it brought to mind a few lines from the critic Pauline Kael. “[S]o many people are beginning to treat ‘youth’ as the ultimate judge—as a collective Tolstoyan clean old peasant,” Kael wrote. “They want to be on the side of youth; they’re afraid of youth.”

This quote is from 1969, and yet, it’s hard to think of a more perfect description of the culture of the past 10 years. Recall the corporate town hall meetings where senior executives vowed to “listen and learn” how to be better people from junior staff half their age; the college president politely begging the student activists who invaded his office bearing a list of diversity, equity, and inclusion demands to, please, let him go to the bathroom; the professional diplomats quailing in ecstatic terror as Greta Thunberg screamed at them from the stage of the United Nations.

They want to be on the side of youth; they’re afraid of youth.

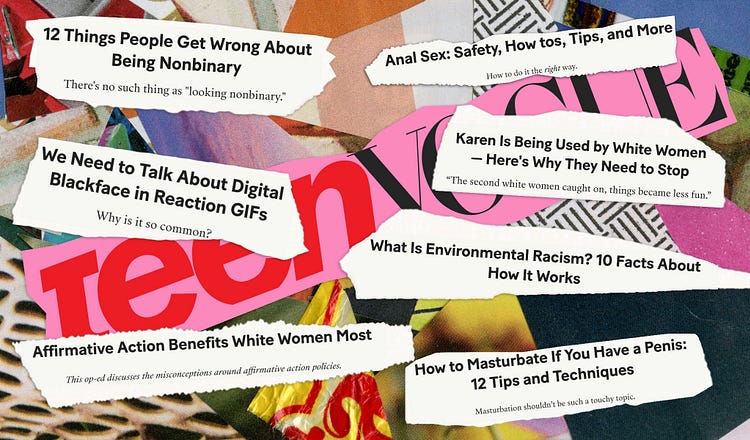

This was also the animating principle of Teen Vogue, which for years has played the role of the radical little sister to the more staid and less political Vogue—whose brand has always been less about the current thing, and more about lavish photo spreads of beautiful celebrities wearing outfits that cost more than my first car. Now, Teen Vogue will be folded into the latter, its site shuttered, and its politics section disbanded; the staffers who churned out stories like “Karen Is Being Used By White Women—Here’s Why They Need to Stop” and “12 Things People Get Wrong About Being Nonbinary” have been laid off.

Reactions were mixed and predictably split along political lines. On the right: celebration, along with the occasional cheeky suggestion that Melania Trump, who was mocked by Teen Vogue’s writers for basically every outfit she ever wore, might have put the magazine on a hit list. From the other side: outrage, as the union representing the Teen Vogue staff issued a conspiratorial statement, declaring that the move was “clearly designed to blunt the award-winning magazine’s insightful journalism at a time when it is needed the most,” and a writer whose X handle includes they/them pronouns and a watermelon emoji mourned the loss of a place for “radical stories about mental health, polyamory, queerness, trans people, and more,” calling the site’s shutdown “nothing short of horrific.”

For both camps, what seems indisputable is that the fall of Teen Vogue is one more sign of an ongoing shift in the media landscape; looking back at the site’s content from the peak of the culture’s Great Awokening is like falling through a wormhole into a past which, though recent, feels like it took place on another planet. There’s an article bemoaning the scourge of “digital blackface”—as in, white people posting reaction GIFs featuring black celebrities. There’s a video of people weeping and shredding Halloween costumes in protest of cultural appropriation. There’s the astonishing guide to anal sex just for teens in which the word “women” does not appear once, though there’s a whole section about how a “non-prostate owner” can enjoy the act.