Nick Cave on the Best Children’s Book Ever Written

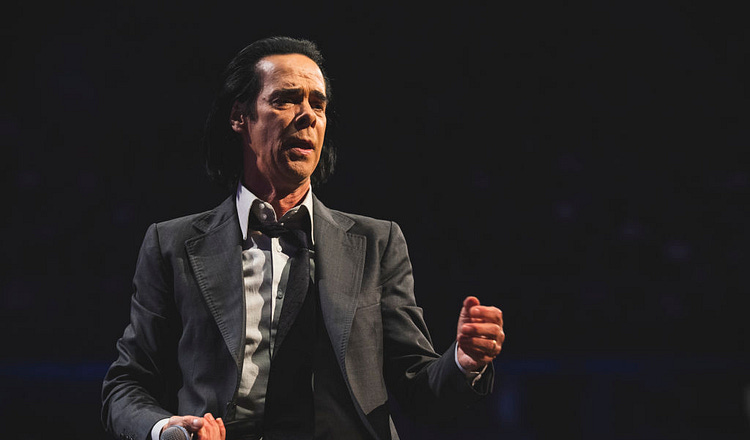

Nick Cave said he found solace in The Adventures of Pinocchio during a dark period in his life. (Photo by Mariano Regidor/Redferns)

The rock and roll legend breaks down ‘The Adventures of Pinocchio.’

32

Nick Cave is a rock and roll legend. If you don’t know him from the decades he’s spent fronting his band, Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, you may recognize his haunting baritone from the theme song of Peaky Blinders.

He’s also a novelist, screenwriter, and voracious reader. And when Old School host Shilo Brooks invited him to select a favorite book to discu…

Continue Reading The Free Press

To support our journalism, and unlock all of our investigative stories and provocative commentary about the world as it actually is, subscribe below.

$8.33/month

Billed as $100 yearly

$10/month

Billed as $10 monthly

Already have an account?

Sign In