JERUSALEM — I was recently at an indoor shooting range in Jerusalem watching new gun-license applicants blast paper targets with mixed success—ordinary people, some rotund guys of early middle age, a man in his 60s with the air of a Talmud professor, a young mother who’d been evacuated from the southern town of Sderot after Hamas terrorists killed dozens of her neighbors on October 7, now living in a cramped hotel room in our city with her husband and two kids.

She fired her rounds with particular intensity, or so it seemed to me, though of course even she couldn’t turn back the clock to October 6. When the instructor was done with her, it was my turn.

The counter at the entrance was swarmed three customers deep—the staff have never seen anything like the last six months. One salesman was explaining the advantages of the Israeli Masada pistol, named, unfortunately, for the site of the mass Jewish suicide that ended our previous stretch of sovereignty here in 73 CE. A religious woman in a skirt, her hair covered with a scarf, was trying out a stomach holster that could be concealed under her shirt—she’s a kindergarten teacher and doesn’t want to frighten the children.

The traditional Israeli attitude to guns is often misunderstood, particularly by observers peering through an American lens. Guns are visible everywhere here, and many visitors, startled by the sight of heavily armed young men and young women in uniform carrying M-16s on the bus or at the bar, assume an enthusiasm for weapons and a free approach to acquiring them.

But Israelis have no legal right to bear arms, no fear of government tyranny in the American tradition, and a fraction of the crime fears that Americans accept as normal. (In an ordinary year, Jerusalem, a city of nearly one million residents, tends to see about a dozen violent deaths; in Indianapolis, a slightly smaller city, the homicide number tends to be over 200.)

For the average Israeli, guns are simply a tool for protection against the Arab violence that has shaped this society over the last century. Like the army, they’re a necessary evil. Most of the armed people you’ll see in an Israeli city are soldiers or police. In the United States, according to a Pew study last year, 32 percent of citizens own guns. In Israel, it was under 2 percent.

That was before October 7.

Since the attacks, more than 300,000 Israelis have requested gun permits—twice the total number of people who owned guns before. In the Tel Aviv area, the number of permit requests rose 800 percent. This may be the most visible symptom of the way our sense of safety has been shattered. For me, the change is manifest in the form of a small Glock—an ugly little monument to a change for the worse in this country and in the lives of its citizens.

Though buying a handgun here has become easier, gun ownership is still tightly restricted and involves paperwork beyond the wildest dreams of gun-control advocates in the United States. If you’re cleared for a permit by the Ministry of Internal Security after a background check of your medical and psychological records, and of your military service, and then pass a test that includes firing 100 bullets, you’re licensed to own and carry a single weapon with a serial number registered with the government under your name. You cannot buy another gun. You’re allowed to buy 100 bullets that must be accounted for each time you renew your license. It’s virtually impossible to buy a rifle.

I went through all of this after October 7, but found the real process to be less bureaucratic than psychological. I was trained to use an automatic rifle in the infantry during my mandatory army service, but like all of my friends I was happy to give the thing back. I didn’t believe that lethal force was necessary in civilian life. By the time I filled in the forms after the Hamas attack, with several acquaintances dead and one captive in a Hamas tunnel, my wife, Naama, had stocked our apartment with water, food, and batteries in case the war spread to Jerusalem. Naama can’t even look at the gun. But nightmare scenarios had been proven realistic, and it seemed irresponsible not to take every precaution.

The early Zionist movement sought to create Jews who could fight, but hoped they wouldn’t have to and certainly wouldn’t want to. In contrast with the militarism that some external observers imagine here in Israel, to a large extent this attitude remains officially in place. There are no military parades, for example. The army tends to avoid warlike symbols and language, preferring euphemisms drawn from the natural world—I once served, for example, at a grim firebase in Lebanon called Outpost Pumpkin, where the weapons systems included a radar known as Buttercup and night-vision gear called the Artichoke. When famous Israeli generals like Moshe Dayan were asked their profession, they’d say they were farmers.

The truth is that for the Israeli urban middle class, which has always been identified politically with “the left,” there has always been something déclassé about carrying a handgun. It’s an object associated with what Israelis think of as “the right,” a term that suggests lower-income voters, and also gun-wielding fanatics like Itamar Ben-Gvir, who was appointed the Cabinet minister in charge of police when this government came to power and who has led the drive to arm civilians. (In Israel the terms left and right don’t mean what they mean in the United States and have never had anything to do with gun rights: they chiefly denote differing attitudes toward compromise with Israel’s enemies, and are in fact often related to whether one’s grandparents ran away from Christian Europe or the Islamic world.)

Part of the dynamic around weapons here is one where the middle and upper classes outsource violence to people further down the economic food chain, and then look down on them for it. A more extreme version of this exists in America, where better-off citizens can express disgust with the military or call to “defund the police,” enjoying the perks of a powerful country and safe neighborhoods while pretending their own hands are clean.

For years, we have suffered regular episodes in which Palestinian men go berserk in public places with knives or guns, killing people until they themselves are shot and killed by security forces or an armed civilian. (The most recent instance occurred last week, when a Palestinian stabbed three people at a mall.) But this never translated into gun ownership, certainly not among people I know. We seemed to expect someone else to be on hand to protect us.

Jerusalem, where I live, and where more than one-third of residents are Palestinian, is particularly susceptible—without even consulting the internet, I can think of a dozen such attacks in the last year. And yet, in the panic after October 7, when one of my neighbors in our building’s WhatsApp group asked how many of us owned guns, the answer was none.

This was obviously going to have to change as we absorbed two lessons of the Hamas attack.

The first was that we could not afford any further delusions about the intentions or capabilities of our Palestinian neighbors. These delusions had just led to the deaths of 1,200 Israelis like us, many of whom were murdered in their kitchens and living rooms, and to the kidnapping of 250 more, with enthusiastic support across the Palestinian public.

The second lesson involved our basic assumption that security forces would always arrive fast. The massacres around Gaza occurred barely an hour’s drive from Tel Aviv, but I met a woman from one southern kibbutz who was rescued by Israeli soldiers only 30 hours after the attack began, during which time many of her neighbors were killed or taken hostage. If a half-dozen Hamas pickup trucks were to come out of the Arab neighborhoods a few minutes away from mine and try something similar, we’d be on our own.

It was around this time that my friends began applying for gun permits, including a psychologist, a radio journalist, a specialist in medieval Jewish history, and a professor of Greek philosophy. And it was around this time that I, like other people I know, found myself calculating angles of fire inside my own home. What can I hit from the stairs? Could the front door stop a bullet? Whatever the outcome in the Gaza war, it was clear that we had already suffered some kind of spiritual defeat.

In Israel, guns are less a matter of personal liberty, as in America, than of communal defense—which is logical, I suppose, in a country whose ethos was forged not by frontier individualists but by socialist kibbutzniks. I recently attended a training session for new gun owners from central Israel, one of whom was Doron Ben-Avraham, 60, from the town of El’ad. This town was the scene of a gruesome axe attack by two Palestinians in May 2022, and one of the three people killed was someone he knew. “If I see a neighbor getting attacked, I want to be able to help—I’ll feel sick if I didn’t,” Ben-Avraham said, reflecting what seemed to be the approach of the twenty men in the class. He applied for a gun permit after October 7 and was now the new owner of a Glock-19.

The class was run by a shooting instructor named Boaz, an IDF counterterrorism instructor who asked me not to use his last name. He’s been doing this for 20 years. Amid the general scramble for weapons, Boaz has been surprised to see the number of new gun owners among the ultra-Orthodox, he said, a community that generally holds anti-militarist attitudes and is happy to leave their own defense to others, and also among women. Sure enough, when the first group dispersed and the next one arrived, it turned out to consist of a dozen women in their 30s and 40s. I found them on plastic chairs discussing the upsides of the Sig Sauer. When I asked them about their motivation, the scenario mentioned most often was an invasion of their home by a killer, the stuff of horror films and of Israeli reality circa 2024. The word that recurred in their answers was control.

The decision to expand private gun ownership is certain to have unintended consequences, and not just because the number of guns will mean more accidents, homicides, and armed extremists. At the shooting range where I got my license, it was clear that some of the new owners were hardly competent to use a weapon in the sterile condition of the range, let alone in an actual attack where we would have to make life-or-death decisions in a matter of seconds while beset by adrenaline and fear. Those with combat training have a chance, though no guarantee of success. When I came home with my new license and a Glock 43X, I told my kids that if they’re ever near a shooting attack they need to lie down flat and wait until it’s over—the main danger being less the terrorist than other Israelis who will open fire and hit something other than their target.

One incident in particular has become a case in point. On November 30, two Palestinians from Sur Baher, a Jerusalem neighborhood near mine, began shooting Jews waiting at a bus stop, murdering three of them before a lawyer named Yuval Castelman, who happened to be passing by, jumped out of his car with his handgun. He engaged the terrorists with admirable bravery—only to be mistaken for a terrorist himself and killed by an army reservist exercising something between bad judgment and criminal negligence. Guns solve some problems and create many others. It’s hard to say how we’ll remember all of this in a decade or two.

But even in the weeks of my work on this essay, an Israeli with a handgun managed to kill a terrorist, another Palestinian from Jerusalem, who was shooting innocent people on a road in southern Israel, two of whom died. That was on February 16. On March 14, a noncommissioned officer waiting in line at an Aroma café didn’t notice the Palestinian kid in a black sweatshirt who lunged at his neck with a knife—but did manage to draw his handgun and shoot the assailant, preventing more fatalities, before he bled to death.

A friend from America told me recently that every Jewish person he knows has a contingency plan, sometimes secret or scarcely admitted even to themselves, for where to hide or escape if things get really bad in the diaspora—the kind of thought borne of a good education in Jewish history mixed with a close read of current events, like aggressive protests outside synagogues, shots fired at Jewish schools, and the growing fever about “Zionists.”

Mulling this, I asked friends here in Israel if they had a similar plan. No one did. Zionism has clearly failed to change everything in the Jewish condition, but it seems to have changed that, for what it’s worth. I don’t know anyone preparing a hideout. But I do know a remarkable number of people with a new Glock.

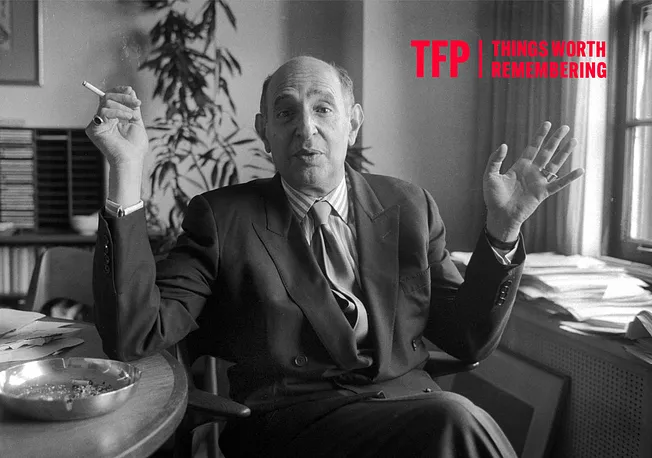

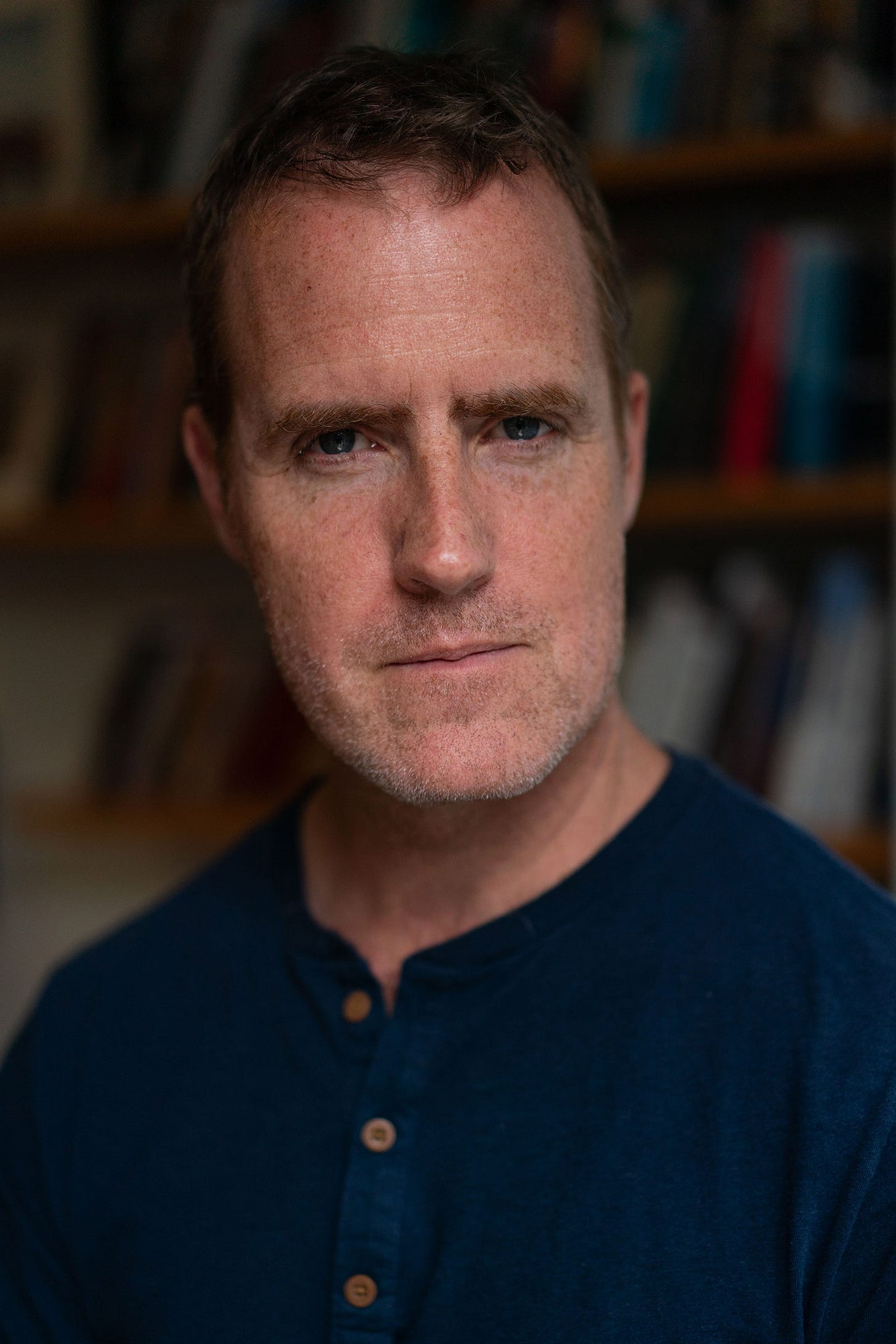

Matti Friedman is a Jerusalem-based columnist for The Free Press. He’s the author of four nonfiction books, including most recently, Who by Fire: Leonard Cohen in the Sinai. Read his Free Press piece “The Wisdom of Hamas,” and listen to his talk with Bari on Honestly about the time Leonard Cohen visited Israel during the Yom Kippur War. Follow him on X @MattiFriedman.

Become a Free Press subscriber today: