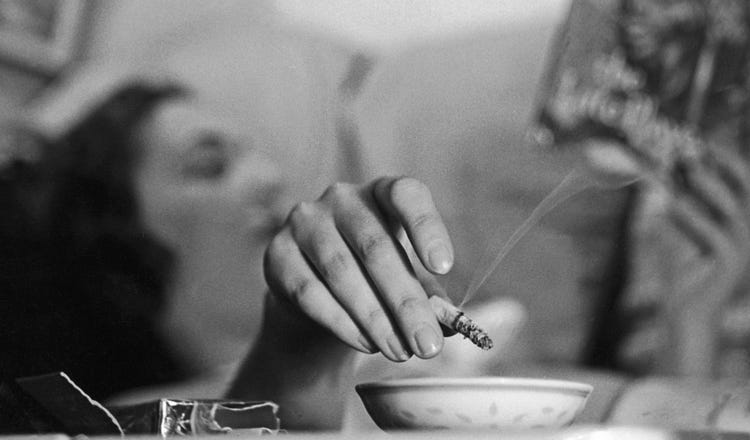

When I first met Michael Moynihan, more than a decade ago now, he pretty much always had a cigarette in his hand. I know I’m not supposed to say this, but he did look cool.

Back then, we worked together on book reviews he wrote for The Wall Street Journal and also on some scoop-ey stories, like this one for Tablet.

Now Michael is a co-host of The Fifth Column podcast and a national correspondent for Vice News. He quit his favorite vice—smoking—as you’ll read about below. He’s still cool, and hopefully will be around much longer now that he gave up on the cigs. — BW

In 2017, after an adulthood of joyful and guiltless tobacco consumption, I abruptly quit smoking. This was an improbable outcome; I rather enjoyed smoking and rarely made threats to give it up. But having seen enough friends and family members die with a vigorous assist from Big Tobacco, I decided that upon publication of a book review in The Wall Street Journal, in which I praised an obscure German writer’s memoir of nicotine addiction and reluctant abstinence, I would try my hand at teutonic discipline and finally ditch the smokes.

In that review, I hinted at the inevitability of cessation, explaining that “when I conquer smoking it will be equally in response to the devastating health effects of the habit and the unrelenting social pressure.” It was time to quit because society told me so, not my lungs. And while I opposed the dreary moralism of the anti-smoking crowd, I had to acknowledge that, on the macro level, they had a point: Death was perhaps too high a price for the occasional pleasure of a cigarette.

The inevitability of a smoking-related death has been known, with varying degrees of medical certainty, since the widespread adoption of smoking in the 1920s. Prior to the social stigmatization of smoking, many of us only considered quitting to appease those who pointed to the actuarial tables, reminding us that we would be called upon to dispense money, life lessons, and fatherly advice.

But on our own, unencumbered by children and in spite of the busybodies, many smokers simply don’t mind the risk, reassured by a grandparent who survived D-Day and a few hundred thousand Lucky Strikes. Way back in 1995, Cornell professor Richard Klein, author of Cigarettes Are Sublime, pointed out that different humans might desire different life outcomes but “healthism in America has sought to make longevity the principal measure of a good life.”

But longevity sounded pretty good to me. The day my Wall Street Journal review was published, the postman showed up with a package from the San Francisco-based electronic cigarette manufacturer Juul; a buffet of flavored nicotine pods, branded with a promise to wean me off toxic combustible cigarettes.

I haven’t had a single cigarette since.

But now, five years later, I’m skulking around Manhattan’s Canal Street, finding my nicotine fix at a windowless shop owned by enterprising immigrants, ready to sell me illegal nicotine products.

That’s because in 2019, New York state, always a leader in legislative sophistry, prohibited the sale of flavored electronic cigarettes because, the argument went, kids love tasty things and adults don’t. The New York law emboldened prohibitionists at the FDA, who on June 23 ruled that while traditional cigarettes, with all of their carcinogenic promise, are still available to adults, Juul was to be shut down by government fiat. (The next day, the U.S. Court of Appeals in Washington, D.C., blocked the FDA order, giving Juul a temporary reprieve. Earlier this month, the regulatory agency agreed to conduct an additional review of Juul.)

Incompetent bureaucrats. Moralizing politicians. Dubious scientific claims. Frequent invocations of “the kids.” The government’s war on Juul has been a perfect storm of regulatory overreach.

Despite any available evidence suggesting that Juul would kill Americans with the alacrity of Marlboro Lights, beginning in 2018 the FDA attacked the company with a bizarre single mindedness, as did various state attorneys general. The allegation was that flavored vaping products were hooking a new generation of kids who would have otherwise gone to church, done yoga, and drank wheatgrass smoothies. It’s the oldest puritan trick in the book: If you want to ban something, claim that you seek its abolition in the interest of “the children.”

It worked. In 2019, the company “voluntarily” stopped selling flavored vaping products, pushing me towards surreal interactions with dealers promising, for an unreasonable fee, access to bootleg mango Juul pods.

Strangely, banning a product enjoyed by millions didn’t make it go away.

The evidence of the harm done by Juul’s products is scant, especially when compared to highly toxic combustible cigarettes. But the anti-Juul moral panic was given an assist by media puritans, who wrote countless nearly identical stories—often in nearly identical language—who amplified every shoddy study claiming vaping might even be as bad as smoking (many of which have been ably debunked by Dr. Michael Siegel of Tufts University Medical School). It became something of a requirement for reporters to describe the device as being “cool,” “resembling a USB drive,” and warning the students were being ensnared by “kid-friendly flavors” like . . . cucumber.

It was a coolness that could only be imagined by horribly uncool journalists. One could hardly imagine Keith Richards—who looks surprisingly cool when hacking and wheezing his way through a guitar solo, smoke dangling from his lower lip—exhaling plumes of vegetable-flavored glycol vapor drawn from a flashing memory stick.