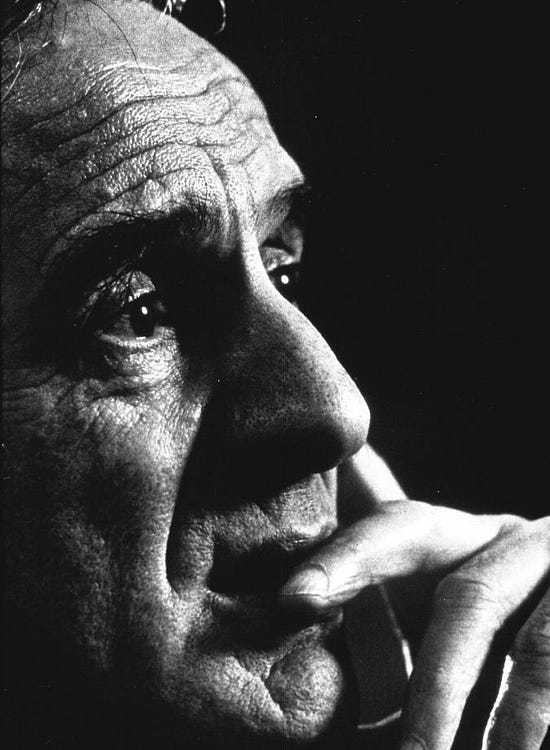

I was born in East Germany in 1964 and grew up behind the Iron Curtain. For most of my life, Holocaust survivors were living reminders of something incomprehensible, something that, out of shame, was rarely talked about in the country of my birth. The name of the acclaimed writer Elie Wiesel, for instance, evoked the horrific images of Auschwitz that invariably force me to avert my eyes.

But then I moved to America—and Elie Wiesel became my patient.

My home, Oranienburg, a sleepy town just north of Berlin, has found only dismal fame as the home of the former concentration camp Sachsenhausen. Like most students in East Germany, I was a member of the Young Pioneers, a youth organization whose stated mission was to cultivate a generation of “defenders” of socialism. Aside from flag ceremonies and field trips, the curriculum called for students to visit the concentration camp, which was only a short distance from our school. What I saw there has burned itself into my memory: the iron gate emblazoned with the familiar slogan Arbeit Macht Frei (“work sets you free”), barracks overcrowded with wooden bunks and straw sacks, execution installations, and crematoria. All of it enclosed by barbed wire and electric fences.