Ghislaine Maxwell, Elizabeth Holmes and Me

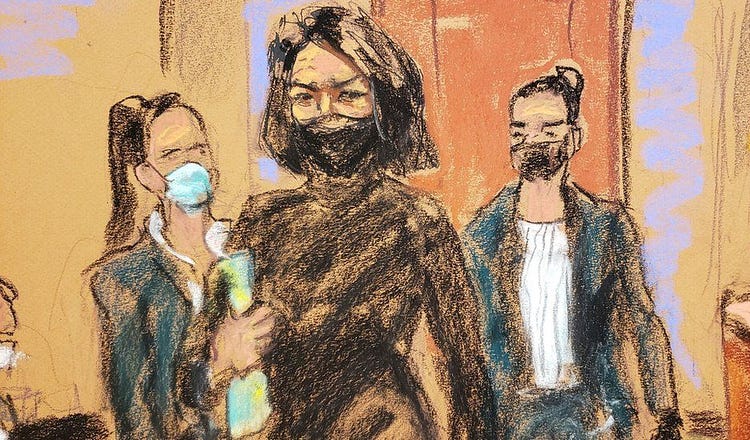

Artist Jane Rosenberg’s sketch of Ghislaine Maxwell's court appearance.

Amanda Knox on why we can't look away from female villains.

134

There are no cameras allowed inside Ghislaine Maxwell’s trial, but that hasn’t stopped me from poring over every sketch of the courtroom scene, and analyzing each kernel of evidence that emerges.

Meanwhile, there are a lot of people on trial for alleged wire fraud and a lot of scammers in Silicon Valley. None of them are as interesting to me as Elizabet…

Continue Reading The Free Press

To support our journalism, and unlock all of our investigative stories and provocative commentary about the world as it actually is, subscribe below.

$8.33/month

Billed as $100 yearly

$10/month

Billed as $10 monthly

Already have an account?

Sign In