On January 3, U.S. troops landed in Venezuela’s capital and captured Nicolás Maduro in the middle of the night. The world was shocked when it saw the first images of Maduro, wearing a gray tracksuit, blindfold, and handcuffs, getting flown out of the country.

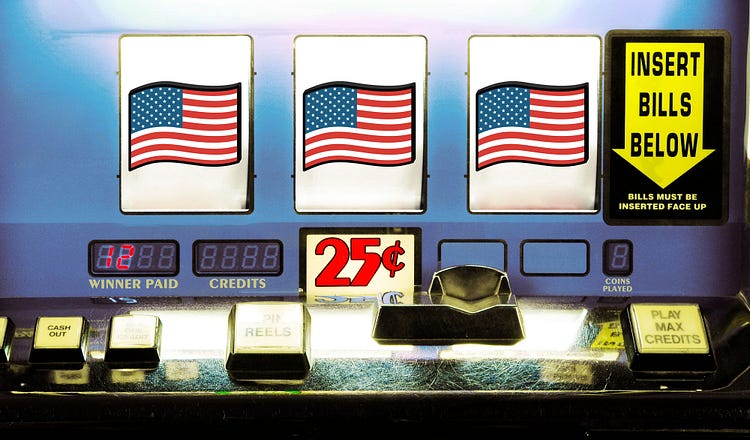

But to one bettor on Polymarket, a cryptocurrency-based prediction market, the news may have been less surprising. The bettor, whom we know only by the username “Burdensome-Mix,” had created an account weeks earlier, and had placed a series of small bets on events in Venezuela. Then, hours before U.S. troops got to Caracas, the anonymous trader placed a $32,000 wager that Maduro would be out of power before January 31. The bet paid out about $400,000, a 12-fold profit in a matter of hours.

Soon after his big win, “Burdensome-Mix” deleted his account, leaving many to wonder who the bettor was, what he might have known about Maduro’s capture, and how he knew it.

Prediction markets like Polymarket are a project that has been more than three decades in the making. When the idea was first bandied about around 1990 by Robin Hanson, an economist now at George Mason University who is seen as the father of prediction markets, it seemed like the most outlandish of economic exercises. Hanson believed prediction markets could solve everything from government spending to colonizing Mars. Hanson speculated that having citizens bet on their preferred political outcomes—a form of government he dubbed “futarchy,” a portmanteau of future and anarchy—could be a better way of governing than voting.