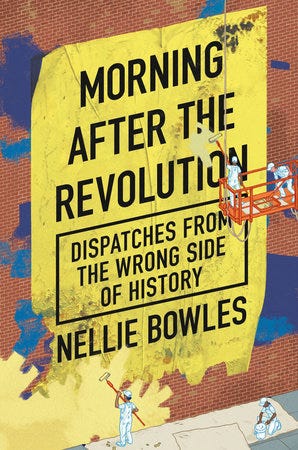

TGIF, everyone. This week is a special edition. It’s an excerpt from my forthcoming book, Morning After the Revolution, which your local bookstore will certainly refuse to stock, so good luck out there. Next week we’ll have a double-wide Where I TG. Until then, comfort yourselves with these TGIF socks, new in our merch store.

Now, about the excerpt. You know me as your devoted, unhinged, and very happy news narrator, as a mother, a wife, and of course, as a debutante. But it wasn’t always this way. When I refer to my youthful Hamas days, I’m being very close to serious. Because before 2019, before the revolution decided to do things that impinged on my life and freedom, I was a committed party member. I was good at it. Though it doesn’t take much skill: the American media class chants a group chant, and all you have to do is join whatever’s trendy that week.

The book, in the end, is about how I decided not to join. It’s not a heroic story. There wasn’t a single a-ha moment for me. I wasn’t early to this Chic “I’m not a party member” Lifestyle. It was just that, as the demands for the chants grew louder and more insistent, and the rules became stricter and less forgiving, I realized it was demanding I sacrifice things I was not willing to give up. The revolution was telling me: don’t report on anything unless it specifically helps our political candidate of the day and don’t fall in love with anyone outside our boundaries. I failed at both.

The excerpt I’m sharing with you today is about canceling a friend. It’s about falling in love with Bari. And it’s about the end of my time as a good soldier. I’ve been told that the book doesn’t make me look great—and this part certainly doesn’t. I’m okay with that. First, I think it’s important to document the passions and motivations of at least some of the people in this movement (everything is copy). I’m also a big believer in the value of changing your mind when you encounter new information. And in the end, the journey brought me to this column, which brings me more joy than is probably appropriate to admit.

And now, on to the excerpt. And if you like what you read, you can preorder it from the good folks at Bookshop here. The Free Press gets a kickback for every book sold, so maybe you should buy two.

The first time I was consciously part of canceling someone, it felt incredible. I do remember the pleasure.

The situation was pretty clear-cut: a close friend was canceling someone, and I could help.

My friend was a writer and generally hilarious person. This friend, who was black, was quoted in a book by a white author, also well known, less hilarious but equally lovely—I’d met her at a couple parties and liked her. This white author had asked me to do a fun and casual onstage interview with her as part of her book tour, and I’d enthusiastically said yes. The event had been announced and posted online.

Then came the fight.

My friend didn’t like the quote when it came out in the book. She posted to her Twitter followers about it. She said the author hadn’t told her she was on the record (the author disagreed). She said she was misquoted and also had no idea she was being interviewed (the author disagreed). It was a shit show. And in the court of public opinion, my friend was winning.

It’s Twitter, not real life. That’s what people say. But for the media class—the people who decide what books go on tour and what books get reviewed, what books you hear about—it’s the artery system. Twitter is where articles get ginned up.

A drumbeat of rage against the author was growing. I felt the rage too. Like someone flagrantly littering or snatching a purse, she’d violated the contract we all made. She’d made an apology, but it had been defensive. If we’d learned anything from anti-racist school, it was that apologies had to be abject and endless. She was pushing back still, a little. People I loved were disgusted, and so was I. White women can’t just take words from a black woman to sell shitty books! The premise of her book was vile anyway. The author was vile. Black lives very much matter, and a random white liberal needs to know that.

My friend never asked me to do anything, but I wanted to defend her. A good ally is assertive and doesn’t need to be asked. Platforming, sitting onstage with this white woman, was endorsing her. I wanted to embarrass her, and I could. I was scheduled to appear onstage with her. I wrote to her, and said I was sorry but I could no longer participate in her book tour. She’d need to find someone else. She asked me to reconsider. I wouldn’t.

I told a lot of friends about that. I was proud. People said I’d done the right thing. To do a cancellation is a very warm, social thing. It has the energy of a potluck. Everyone brings what they can, and everyone is impressed by the creativity of their friends. It’s a positive thing, what you’re doing, and it doesn’t feel like battle, but like tending the warm fire of community. You have real power when you’re doing it, and with enough people, you can oust someone very powerful.

The easy criticism of a cancellation is: You went after someone who agrees with you on almost everything except some tiny differences? Some small infraction? It seems bizarre. But that’s the point. The bad among us are more dangerous to the group. Mormons don’t excommunicate a random drag performer. They excommunicate a bad Mormon.

I watched all the presidential debates in 2016 with some family members who are conservatives. After Hillary lost, I couldn’t stomach going over there for a few months. I was too upset, and I couldn’t handle seeing them happy. But that’s not a cancellation. I had no power over these family members, or sway in their community. I couldn’t make them apologize for being happy that Trump won.

A cancellation isn’t about finding a conservative and yelling at them. It’s about finding the betrayer in your midst. They look and talk like you. They blend in perfectly. But they’re not like you.

The author I canceled existed in my community. She went to the parties I went to and showed up at the same events as me. The goal was to slice her carefully out, and I was thrilled to do my part. By showing where I stood, I felt closer to my friends. But also, in some ways, doing what I did is the price of admission to the club. To ignore the drumbeat was to suggest that I didn’t care. I definitely did care.

I saw later that the event was canceled altogether after I withdrew. Her book tour didn’t work so well. The book didn’t sell so well. I never saw her at another party, and I never heard from her again—and I was fine with that.