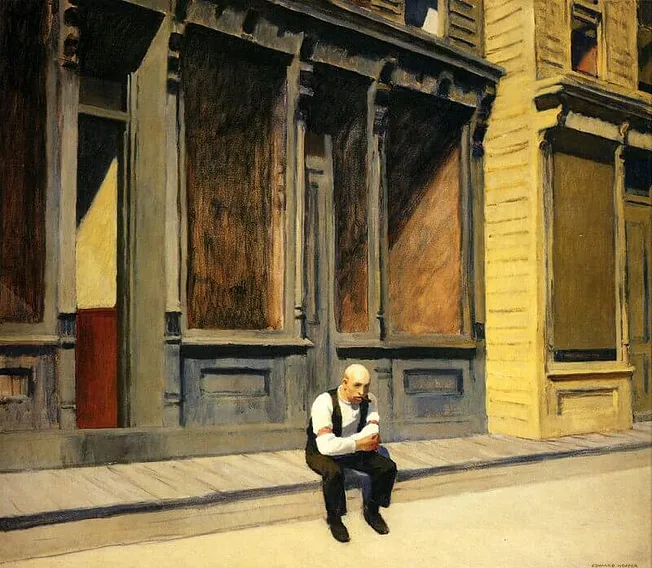

My best friend Mike died alone. That was how he lived, too. He ate alone. He slept alone. Aloneness was his natural state. At age 50, it was sepsis that officially did him in. But really, it was solitude.

Like Mike, America’s white working class is alone. Like Mike, it is being crushed by its isolation.

Since 2000, white working-class Americans between the ages of 45 and 54 have been one of the only demographics in the world that has seen its life expectancy fall. These deaths are mostly suicides. Some are officially blamed on alcoholism and addiction, but that’s just suicide in slow motion. Whatever we call them, they’re a lagging indicator of an economy in transition.

Just as the working class is succumbing to our increasingly digitized, globalized, automated, post-industrial era, the working stiffs—the assembly-line workers, welders, mechanics, miners, and their kin, the people who once made up the working class—are tacitly acknowledging they have no role anymore.

I know this feeling well. It’s where I come from.

I grew up in Memphis and Springfield, Missouri, surrounded by people who gave up. People who died long before it was their time: my dad. My aunt. My uncle. Two of my first cousins. Soon, I fear, my sister, who thought she could marry up to escape her childhood; it turns out the Junior League and fancy cars can’t undo the past.

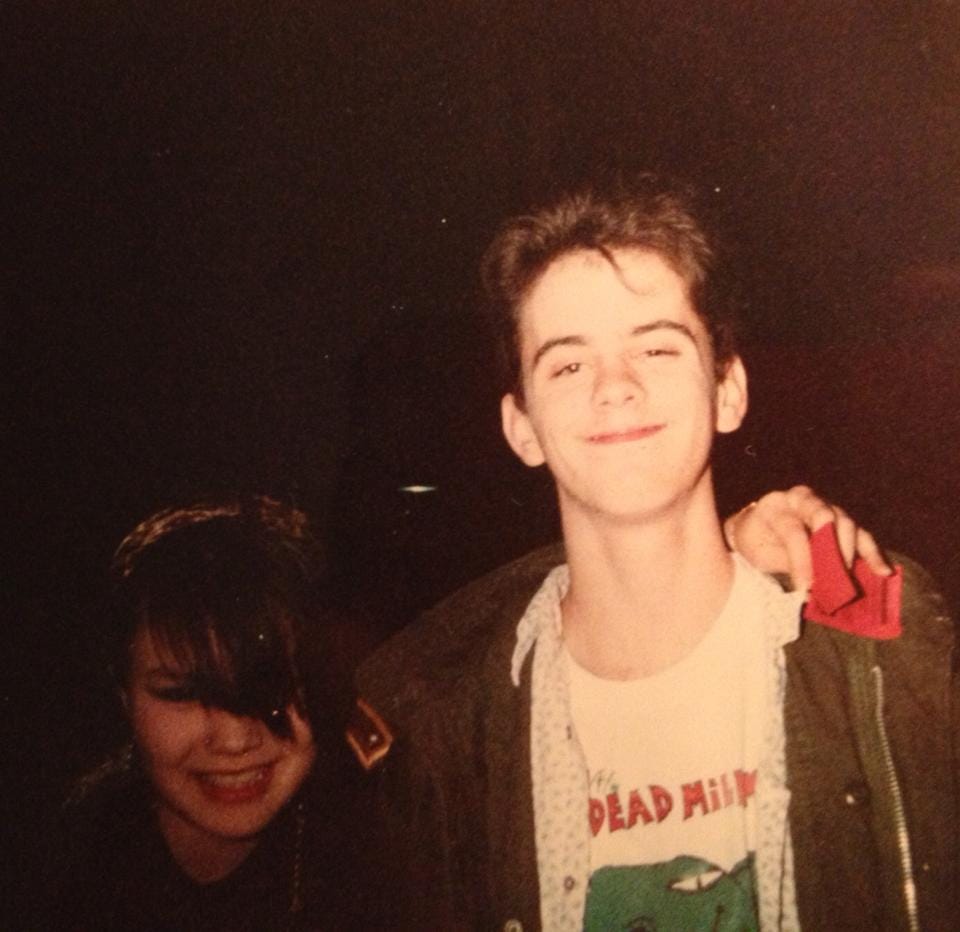

And last month, my best friend, Mike. We met in 1987, when we were 16. We went to different, nearby high schools. We were part of the same angry, alienated, tuned-out, disaffected scene—the kids who weren’t rich or attractive, or jocks; the kids who liked black t-shirts and funky hairstyles, who were like a collective “fuck you” to Ronald Reagan’s America.

By now, this is an old story. We’ve been hearing about “deaths of despair” since 2020, and really, since Donald Trump was elected president in 2016, which zapped our nation’s somnolent elites into taking notice of working-class America’s crisis.

I’m here to report that, seven years later, on the cusp of another presidential campaign, those elites have learned approximately nothing. Republicans have tried to capitalize on our anger and bitterness, and they’ve made great headway—but they offer little in the way of a serious agenda to rectify the cascading crises that have beset the American hinterland: shuttered main streets, shuttered factories, opiates, obesity, the decline of the Protestant work ethic, the giving up. This should surprise no one. How can the party of free markets be expected to fix problems that were mostly created by. . . markets. Democrats, who used to be our party, who remain my party, are our last, best hope, if they can only find their way back to the class-based political space they once inhabited. That remains a very big if. Countless Mikes are depending on them.

Mike—his full name was Michael Moore, like the filmmaker—came of age, like I did, at the intersection of working-class decay and a rapidly liberalizing bourgeois culture.

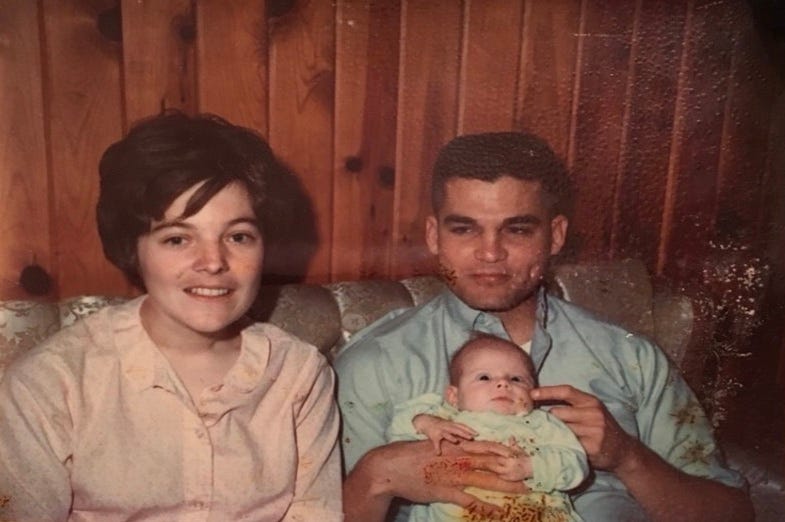

In the early 1980s, his dad, unhappy with his marriage and five kids, pulled the escape lever of no-fault divorce and bolted Springfield, in the Ozarks, for Houston. There he found better-paying jobs and a new family—650 miles away from his youngest son. Mike’s mom, Sandra, moved the family to a cheaper, poorer neighborhood in Springfield. Mike was eight.

Sandra did her best. But the government-subsidized house the family lived in was cramped and unhappy, and by the time Mike entered high school, his four older siblings had fled. Like his dad, they were so busy saving themselves they forgot Mike was left behind. On top of that, the house was on uneven land, and there was standing water at the foundation that led to an ever-present mold. For Mike, that meant allergies. He was an easy target for bullies.

Then there were his mom’s personal woes. She salved her depression with Milwaukee’s Best and an abusive boyfriend—a sullen drunk and Vietnam vet who literally moved into their home uninvited. There he abused Mike and Mike’s mom before a friend intervened. Whether it was physical, emotional, or sexual, Mike would never say.

Back then, in the late eighties, it was Mike and our friend Karl and me. Karl’s mom was never home, so we’d hang out at his place. Lots of drinking and smoking weed and listening to Black Flag, the Smiths, and Crass. (Mike loved Crass’ song “Asylum,” which ends with the lyric “Jesus died for his own sins, not mine.”) A low-rent Breakfast Club minus Molly Ringwald.

In the summers, Mike visited his dad and saw the life that had been denied him but given to his stepbrother. Kent was cocky and handsome and drove a convertible Jeep, and went on to play Division I tennis at the University of Missouri. Back home, Mike drove a junk-bucket Volkswagen Beetle to a sub–minimum wage job at a movie theater in a beat-up mall. Rides came with obligatory Fahrvergnügen sing-alongs. His sardonic warbling of the German “joy of driving” was always tinged with a touch of bitterness.

By now, it’s become orthodoxy among my fellow Democrats that the ticket out of despair is higher education.

There’s a lot of truth to that: since 1979, wages for those with a bachelor’s or postgraduate degree have risen by 22 percent and 28 percent, respectively. Those with only a high school diploma have seen their wages dip by 2 percent; those who dropped out, 18 percent.

But what those college-educated Democrats often can’t see is that a degree isn’t enough. That so many of us who made it to campus never learned the cues, lingos, tastes, and mannerisms of the upper classes, which are, in a way, more important than the degree. That was the subtext of J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy. That was my experience. It was definitely Mike’s.

Mike was industrious. He managed to get himself into the University of Missouri. He was into punk (although he never dressed the part). He loved reading Hermann Hesse. He was fascinated by Germany and the Holocaust. Not in a morbid way, but because he wanted to know what made human beings so indifferent to others’ suffering.

After college, he moved to Dallas to be closer to his dad. He tried to land a job with the Texas Democratic Party, but that never materialized, and he didn’t have the wherewithal to stick it out. He didn’t have anyone telling him that it was going to be all right, that eventually, something good would happen. Instead, he got a job at a car rental company. He hated it.

Panicked, Mike pivoted to computers, where he found steady work building online training classes. He was terrified of poverty and labored tirelessly to pay off student loans and credit card debt.

In our twenties, our roads diverged. I was in grad school by then and starting to build something—a career, a group of friends with like-minded interests. Mike seemed incapable of finding his way, forging friendships, dating.

After two decades of toiling away in a corporate world he had no taste for (and no idea how to succeed in), he settled his debts and saved enough for a modest condominium in a faceless St. Louis suburb. But he had no one to share that with. He had stopped trying to meet a woman by his late thirties. There had been the occasional hookup, but that was it.

He chain-smoked his way into middle age. He seemed resigned to things. He had worked so hard to escape the gravitational pull of his family’s self-immolation, but he didn’t know how to make it happen, and he lacked the confidence—or grit, as TED Talk enthusiasts say—to keep going.

The American left isn’t sure what to make of people like Mike or his family or mine. The white working class used to be the focus of the American left, but the left abandoned us amid the tumult of the late 1960s: Vietnam, the civil rights movement, women’s rights, the radicalization of the campus, the upending of traditional mores and family structures. That was when the paradigm started to shift from a class-based politics to a politics of race and sex. Now, we’re a cudgel used by progressives to bash “late-stage capitalism,” whatever they mean by that.

Over the course of the 1970s and 1980s, as the working class gave way to the titanic economic forces reshaping the United States, we found ourselves increasingly on the margins of the Democratic Party. Bill Clinton briefly cobbled the old coalition back together. It did more good for him than us.

By the early 2000s, the working class was adrift. Thomas Frank’s 2004 What's the Matter with Kansas? made coastal progressives feel better about themselves by blaming their political shortcomings on us, by insisting we’d been duped by GOP culture warriors. If only those dumb working stiffs hadn’t been taken in by the pro-lifers, we could win back the White House. When, in 2008, Barack Obama did just that, progressives took it as evidence that—hey, guess what?—Democrats didn’t need the white working class. Fuck the deplorables.

Then, in 2016, along came Donald Trump. Did he appeal to some people’s darker tendencies? Absolutely. But mostly, they were looking for someone who would pay attention.

Progressives responded to the election by talking about escaping their bubbles in New York and Los Angeles and studying the weird ways of these awful people who had voted for the wrong candidate. It was laughable.

We didn’t need to be studied. We needed to be represented. We needed schools and roads and bridges. And you know what? God and family wouldn’t have hurt either. That didn’t make us fire-breathing conservatives. It made us human.

I was luckier than Mike: I had wonderful grandparents. They had come from Mississippi, and migrated from the farm to small-town life, and my grandfather had been an assistant manager at a wholesale-goods store in Memphis. And when I was 11, and my mother and sister and I had to flee Memphis—my father was a violent son of a bitch; there’s no other way to put it—my grandparents sold everything and came with us to Springfield. While my mother worked two minimum-wage jobs, as a janitor and a clerk at a clothing store, my grandparents gave me structure and a sense of purpose. There was no drinking and no swearing, and we always read the Bible before bed. I’m not a devout Southern Baptist like they were, but that faith still gives me ballast.

Point is, that’s all it was: luck. The luck of having the right grandparents.

When other Democrats ask me what people like me want, I always think the same thing: I want to live in an America where luck isn’t that important. Sure, sometimes you get a lucky break. Sometimes, it’s the opposite. But the bottom doesn’t fall out from under you when someone loses a job or gets sick. In this America, there’s always a safety net and a way forward. There’s a government that says, Here’s some help—now get back to work.

For twenty years, Mike and I spoke on the phone two or three times a week. I badgered him into counseling to deal with his childhood. I begged him to move near me.

Then, in 2017, something inside him finally shattered. For years, he’d say, “I’m in this all alone,” and then, he really was. He slowly broke contact with Karl and me. Calls, texts, and letters went unanswered.

Last October, his mother died. Mike didn’t want to talk, so I texted him my condolences. He texted back: “All things will pass. Tonight, it hit me, though, there is no point in talking. People talk too much—usually to their own detriment.”

A few weeks ago, Karl called. I knew the news before answering. The sepsis had come from acute myeloid leukemia, which doctors blamed on the smoking. Mike ignored his symptoms. His boss drove him to the hospital for testing. That night, after they’d processed the tests, the doctors called him. They wanted to hospitalize him immediately. It was too late. Mike had already died at home. The next day, coworkers noticed he wasn’t there and called the police.

It was a small funeral. A few people from work. A few family members. Kent—who is now married to a woman who, I’m told, comes from a wealthy family with ties to the Texas Democratic Party—couldn’t make it. I tried my best to be polite to Mike’s father.

After the funeral, I kept thinking I was living the life Mike should have lived. He should have gone to grad school. He shouldn’t have listened to his professors who told him getting an academic post would be impossible. He should have found someone who would have appreciated his sense of humor, his musings on literature and popular culture.

Instead, that person is me, even as I am surrounded by more deaths of despair: my Uncle Michael, who drank himself to death in 1982 (he hadn’t yet hit 40); my father, who was a drunk and turned up dead in a motel in Nicholasville, Kentucky, in 2005 (he made it to the ripe old age of 61); my cousin Todd, age 43, who died a few years later of a heart attack while standing in line at a liquor store in Memphis (he’d just checked out of rehab, and the doctors had told him if he drank again, he’d die); and then, a few years after that, Todd’s older brother, Michael (also a drunk; he was 51). My sister, Kim, now 56, is an alcoholic and is barely hanging on; she lives with her husband in the Ozarks. We no longer speak.

It’s strange to live in the echo of all this loss. It’s strange to be in academia. I teach history at a small Catholic school in Erie, Pennsylvania—Gannon University. My focus is American liberalism and genocide studies, and the truth is I don’t belong here. I applied to 200 schools before landing an academic job. My wife, Sam, and I have a daughter and tenure and a dog and a mortgage and each other. During the pandemic, we moved my mom to be near us; she lives a mile and a half away and eats dinner with us four nights a week. I worry, like everyone from a broken place, about losing everything.

We try to anchor ourselves to each other, if not our God, and burrow through whatever happens. But I know that part of burrowing is shutting out what we don’t want to see. I know there is but a microscopic film separating Mike and me. If I ever forget it, this voice—or really, this amalgam of voices, smirking, drunken, vengeful, furious—reminds me not to fly too close to the sun for fear of tumbling all the way down.

Jeffrey Bloodworth is the author of Losing the Center: A History of American Liberalism, 1968-1992.

For more personal essays you won’t find anywhere else, become a Free Press subscriber today:

our Comments

Use common sense here: disagree, debate, but don't be a .