The Humiliating Cross-Examination of SBF

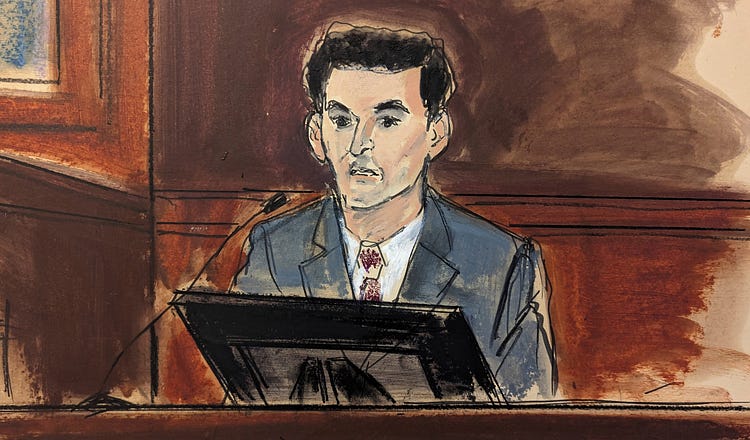

A courtroom sketch of FTX founder Sam Bankman-Fried in Manhattan federal court. (Elizabeth Williams via AP)

“Did you say in private, ‘Fuck regulators?’”

128

The first audience members started arriving around 10 p.m. on Sunday night, even though the event wouldn’t begin for another eleven and a half hours.

The people in line weren’t waiting for Taylor Swift tickets, or some new Apple device, but for a coveted seat in U.S. District Judge Lewis Kaplan’s courtroom in lower Manhattan, where alleged fraudster Sam …

Continue Reading The Free Press

To support our journalism, and unlock all of our investigative stories and provocative commentary about the world as it actually is, subscribe below.

$8.33/month

Billed as $100 yearly

$10/month

Billed as $10 monthly

Already have an account?

Sign In