Jamie Hale has been in and out of the hospital for more than half his life. The 33-year-old Brit needs a wheelchair and relies on partial ventilation and round-the-clock care. Several years ago, he was critically ill and hospitalized for six months “as a direct result of not having had that care,” he told me from the back of a car on his way to a weekly visit at a National Health Service clinic in London. “I’d be dead without the NHS,” he concludes.

Even so, Hale—who has a master’s degree in philosophy, politics, and the economics of health—often thinks about how much his life costs the state. “I’m very aware I’m not cost-effective,” he added. “It’s very hard not to be aware you are the kind of financial burden the system is creaking under.”

Hale is deeply opposed to the assisted suicide bill that the United Kingdom’s Parliament is voting on this week. On November 29, its members will consider whether to advance a bill legalizing assisted dying for the terminally ill with a prognosis of six months or less. If the bill becomes law, an individual could self-administer a lethal drug prescribed by a physician after two doctors and a judge have signed off on the procedure. The bill legalizes assisted suicide, but not euthanasia, which is when someone else—typically a doctor—is the one to kill the patient.

At first glance, the law appears to have little to do with people like Hale. His condition, which he prefers not to specify, is chronic and progressive, but it isn’t terminal. Still, he’s among many disabled people, end-of-life doctors, and concerned citizens who fear the law could put vulnerable people under pressure to end their lives, and start a slippery slope toward future laws allowing euthanasia for the disabled, the poor, and the depressed.

Opponents of the bill include both liberals and conservatives, churchgoers and atheists, disabled and able-bodied, the sick and the healthy. Some have practical questions, such as whether doctors will be able to tell if a patient genuinely wants to die, or if the patient is being pressured into it by a family member angling for an inheritance. Others ask if a country with a strained nationalized health service can help its citizens die without a conflict of interest.

If the law passes, Hale worries it will “change the way we think” about end-of-life care. “It’s going to make it look perhaps increasingly selfish to stay alive in an expensive way.”

The most compelling argument for assisted suicide is that it can prevent a bad death. This is what palliative—or hospice—care is supposed to achieve: giving patients pain relief and symptom management, as well as emotional, social, and spiritual support at the end of life. In modern Britain, bad deaths are common, with one in four people dying without access to palliative care. But even the best palliative care “cannot help some issues,” said Claire MacDonald, director of development at My Death, My Decision, a campaign group that favors assisted dying for terminally ill adults or those who suffer from intolerable pain. For example, according to Britain’s National Institute for Health and Care Research, organizations “are not always set up . . . to deliver the right care, at the right time, for all dying people and their families, in their preferred place.”

Like many doctors who specialize in end-of-life care, Matthew Doré opposes assisted suicide. The honorary secretary of the Association of Palliative Medicine of Great Britain and Ireland, Doré said it’s common for people coming into a hospice to say, “I want to die, kill me now,” but once they have the holistic support they need, that feeling “just melts away, disappears pretty much completely in almost everyone.”

What’s more, assisted suicide does not always lead to a more peaceful death, Doré said. Studies show that complications from the lethal drugs include burning, nausea, vomiting, and regurgitation, severe dehydration, seizures, and regaining consciousness. In Oregon, the annual complication rate is nearly 15 percent, although it’s likely higher given that “patients often ingest the lethal drugs without a healthcare professional present to record complications,” one study reported.

But there is another reason for legalizing assisted suicide: to save money.

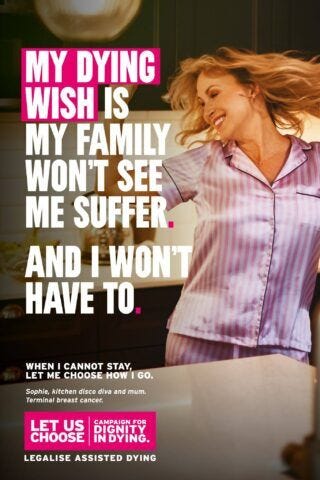

Once the jewel of the UK, the National Health Service has recently been dogged by staff shortages and strikes. A 2024 report found the UK lagging behind 10 other developed countries on hospital wait times. Only Canada had comparably long wait times, while the U.S. was one of the best-performing countries for timely access to care. Now, many in the UK are advocating for assisted suicide as a cost savings measure. Earlier this month, a Telegraph columnist wrote that “assisted dying will leave society financially better off” as well as help “people protect their family wealth.” Earlier this year, a Times of London writer suggested it would be “a healthy development” if assisted suicide for the infirm is “considered socially responsible—and even, finally, urged upon people.” And ads on the London Underground are promoting assisted suicide as a joyful choice, with one poster showing a young woman beaming next to the slogan, “My Dying Wish Is My Family Won’t See Me Suffer. And I Won’t Have To.”

In 2017, one year after Canada legalized assisted suicide, a report estimated the procedure could save the country between $34.7 million and $138.8 million annually. In 2020, ahead of the expansion of Canada’s Medical Assistance in Dying program (MAID) to include those with disabilities and chronic illness, the government projected it would save an additional $62 million a year. At the same time, the number of assisted suicides in the country keeps rising. In 2019, MAID accounted for 5,665 deaths; by 2022, that figure was 13,241. Today, MAID is at least the fifth leading cause of death in Canada.

The final year of a person’s life is the most expensive in terms of medical bills, but assisted suicide is “a hell of a lot cheaper,” Doré said. A 2022 Lancet report entitled “The Value of Death” shows that “between 8 percent and 11 percent of annual health expenditure for the entire population is spent on the less than 1 percent of people who die in that year.”

But Wes Streeting, the UK’s Health secretary, worries that assisted dying will come at the expense of NHS funding in other areas. Palliative care in the NHS currently receives only 37 percent of funding from the state, the rest coming from charity. Assisted suicide would be entirely state funded.

And Lydia Dugdale, a medical ethicist at Columbia University, told me that “getting rid of those who are drains on the system” is reminiscent of Nazi Germany when the disabled and elderly were targeted for extermination. “For people who know their history,” she said, “it almost feels like eugenics.”

Jamie Hale agrees. “If you are genuinely saying these people are too expensive to keep alive, and for that reason we should be killing them, then you’ve completely crossed the moral Rubicon that can’t be defended,” he said. “That’s just pure eugenics . . . I don’t think it’s even worthy of a response in a civilized society.”

Across the West, assisted suicide is increasingly seen as a valid medical solution to physical, mental, and even social problems like a lack of housing or loneliness. In the Netherlands, suicide is being used as a “cure” for mental illness. In Canada, depressed patients can be approved without their families’ knowledge. In Colorado, patients have been helped to die because they have anorexia. And in Belgium, children have been euthanized, raising serious concerns about consent.

Meanwhile, UK polls show support for assisted suicide is growing. Nearly two-thirds of the British public say it is “acceptable to break the law to help a friend or loved one who wants to die.” And some say the NHS might already be encouraging people toward an untimely death. During the pandemic, Paula Peters, 53, was one of hundreds of people who discovered her doctor put a “do not resuscitate”—or DNR—notice on her medical records without her knowledge. After Peters discovered the DNR on her records, she had to fight for nine months to get it removed, she told The Free Press.

“My doctor thought I was disposable and expendable because I was clinically extremely vulnerable, and that had a profound impact on me,” said Peters, who has rheumatoid arthritis and other disabilities. “I’m not a piece of rubbish you can just toss aside.”

The future of the UK bill currently hangs on a knife’s edge. At this writing, there are 176 members of Parliament who have said they’ll vote against it on Friday, 169 who have said they’ll vote for it, and more than 100 who have yet to make up their minds.

If it becomes law, Hale worries that a society uncomfortable with disability will suddenly have more justification to remove people like him from it. “If you live long enough, you will probably become disabled,” he said. “People don’t necessarily want to engage with that. We are the future that they’re terrified of.”

Madeleine Kearns is an associate editor at The Free Press. Read her piece “She Was Arrested for Praying in Her Head,” and follow her on X @MadeleineKearns.

For another smart take on current events, read Josef Joffe's piece, “Jews Are Being Told to Hide in Berlin. Again.”

To support independent journalism, subscribe to The Free Press:

our Comments

Use common sense here: disagree, debate, but don't be a .